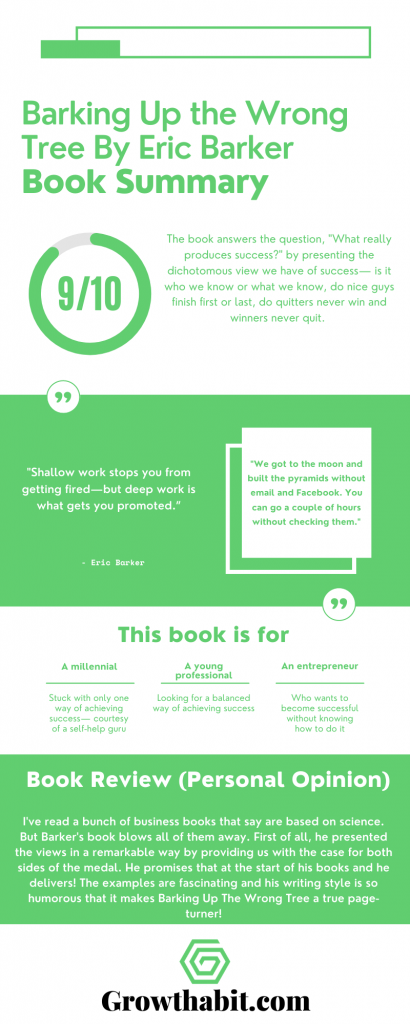

The book answers the question, “What really produces success?” by presenting the dichotomous view we have of success— is it who we know or what we know, do nice guys finish first or last, do quitters never win and winners never quit.

Book Title: Barking Up the Wrong Tree: The Surprising Science Behind Why Everything You Know About Success Is (Mostly) Wrong

Author: Eric Barker

Date of Reading: July 2017

Rating: 9/10

What Is Being Said In Detail:

Barking Up The Wrong Tree is divided into six chapters. Every one of those chapters presents us with two opposing ideas for success. Barker then presents the case for both sides and lets you decide on your own at the end of the chapter which is more important (for you and your context).

Chapter 1 asks if we need to play it safe to win or do we need to be risky. Barker gives us multiple examples such as valedictorians’ who never become millionaires and people who compete and win in the toughest race in the world— Race Across America which is 3000 miles long.

Chapter 2 asks if nice guys finish last…or first. Barker gives us examples of this dichotomy by presenting a case of a neurosurgeon coming from poverty in Mexico and trust, cooperation, and kindness that comes from street gangs and serial killers.

Chapter 3 asks if quitters never win or winners never quit. Barker gives us examples of NAVY SEALs, video games, and even Batman to prove his point.

Chapter 4 asks is it who you know or what you know. Barker gives us examples of top comedians, hostage negotiators, and a mathematical genius.

Chapter 5 asks if we need to believe in ourselves to succeed or not—when the line of confidence becomes a delusion. Barker gives us examples of chess masters, military units, and fake martial artists.

Chapter 6 asks do we need to work, work, work, or find a work-life balance to succeed. Barker gives us examples of professional wrestlers, Buddhist monks, Spiderman, and even Genghis Khan.

Most Important Keywords, Sentences, Quotes:

Two men have died trying to do this.

Outside Magazine declared the Race Across America the toughest endurance event there is, bar none. Cyclists cover three thousand miles in less than twelve days, riding from San Diego to Atlantic City.

…Robič would throw down his bike and walk toward the follow car of his team members, fists clenched and eyes ablaze. (Wisely, they locked the doors.) He leaped off his bike mid-race to engage in fistfights . . . with mailboxes. He hallucinated, one-time seeing mujahedeen chasing him with guns. His then-wife was so disturbed by Robič’s behavior she locked herself in the team’s trailer.

Chapter 1: Should We Play It Safe and Do What We’re Told If We Want To Succeed?

There was little debate that high school success predicted college success. Nearly 90 percent are now in professional careers with 40 percent in the highest tier jobs. They are reliable, consistent, and well-adjusted, and by all measures the majority have good lives. But how many of these number-one high school performers go on to change the world, run the world, or impress the world? The answer seems to be clear: zero.

Grades are, however, an excellent predictor of self-discipline, conscientiousness, and the ability to comply with

rules.

School has clear rules. Life often doesn’t. When there’s no clear path to follow, academic high achievers break down.

…the reason for the inconsistency in the research was there are actually two fundamentally different types of leaders. The first kind rises up through formal channels, getting promoted, playing by the rules, and meeting expectations. These leaders, like Neville Chamberlain, are “filtered.” The second kind doesn’t rise up through the ranks; they come in through the window: entrepreneurs who don’t wait for someone to promote them; U.S. vice presidents who are unexpectedly handed the presidency; leaders who benefit from a perfect storm of unlikely events, like the kind that got Abraham Lincoln elected. This group is “unfiltered.”

When I spoke to Mukunda, he said, “The difference between good leaders and great leaders is not an issue of ‘more.’ They’re fundamentally different people.”

Glenn Gould was such a hypochondriac that if you sneezed while on a phone call with him, he’d immediately hang up.

His neuroses-fueled obsessiveness paid off. By the young age of twenty-five, he was performing on a musical tour of Russia. No North American had done that since before World War II. At twenty eight, he was on television with Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic. By thirty-one, he was a legend of music. Then he decided to vanish. “I really would like the last half of my life to myself,” Gould said. At thirty-two, he stopped performing publicly altogether. All told, he had given fewer than three hundred concerts. Most touring musicians do that in just three years.

Why were the kids with this “bad” gene so inclined to help, even when they weren’t asked? Because 7R isn’t “bad.” Like that knife, it’s reliant on context. 7R kids who were raised in rough environments, who were abused or neglected, were more likely to become alcoholics and bullies. But 7R children who received good parenting were even kinder than kids who had the standard DRD4 gene. Context made the difference.

While Michael Phelps can be awkward on terra firma, Glenn Gould seemed positively hopeless in polite society. But both of them thrived, thanks to the right environment.

As John Stuart Mill remarked, “That so few now dare to be eccentric, marks the chief danger of our time.” In the right environment, bad can be good and odd can be beautiful.

Andrew Robinson, CEO of famed advertising agency BBDO, once said, “When your head is in a refrigerator and your feet on a burner, the average temperature is okay. I am always cautious about averages.”

Chopping off the left side of the bell curve improves the average but there are always qualities that we think are in that left side that also are in the right.

If you’re good at playing by the rules, if you related to those valedictorians, if you’re a filtered leader, then double down on that. Make sure you have a path that works for you. People high in conscientiousness do great in school and in many areas of life where there are clear answers and a clear path. But when there aren’t, life is really hard for them. Research shows that when they’re unemployed, their happiness drops 120 percent more than those who aren’t as conscientious. Without a path to follow they’re lost.

If you’re more of an outsider, an artist, an unfiltered leader, you’ll be climbing uphill if you try to succeed by complying with a rigid, formal structure. By dampening your intensifiers, you’ll be not only at odds with who you are but also denying your key advantages.

When you choose your pond wisely, you can best leverage your type, your signature strengths, and your context to create tremendous value. This is what makes for a great career, but such self knowledge can create value wherever you choose to apply it.

Chapter 2: Do Nice Guys Finish Last?

People surveyed say effort is the number-one predictor of success, but research shows it’s actually one of the worst.

Eighty percent of our evaluations of other people come down to two characteristics: warmth and competence. And a study from Teresa Amabile at Harvard called “Brilliant but Cruel” shows we assume the two are inversely related: if someone is too nice, we figure they must be less competent. In fact, being a jerk makes others see you as more powerful. Those who break rules are seen as having more power than those who obey.

So what happens when all of us become selfish and just stop trusting one another? The answer to that question is “Moldova.”

What garnered this little-known former Soviet republic such a dubious distinction? The Moldovans simply don’t trust one another. It has reached epic proportions, so much so that it stifles cooperation in almost every area of Moldovan life. Writer Eric Weiner notes that so many students bribe teachers for passing grades that Moldovans won’t go to doctors who are younger than age thirty-five, assuming they purchased their medical degrees.

There are three categories: “right,” “wrong,” and “everybody does it.”

Studies show expecting others to be untrustworthy creates a self-fulfilling prophecy. You assume they’ll behave badly, so you stop trusting, which means you withhold effort and create a downward spiral. It’s not surprising that work teams with just one bad apple experience performance deficits of 30 to 40 percent.

…crime creates street gangs. Similarly, the majority of successful prison gangs on record were created not as a way to further evil but as a way to provide protection to their members while incarcerated.

You may be a pirate at heart yourself. Ever get tired of a bully of a boss and think about striking out on your own? Think everyone should have a say in how the company is run? Think a corporation is obligated to take care of its people? And that racism has no place in business? Congrats! You’re a pirate.

Then I looked at the other end of the spectrum and said if Givers are at the bottom, who’s at the top? Actually, I was really surprised to discover, it’s the Givers again. The people who consistently are looking for ways to help others are overrepresented not only at the bottom but also at the top of most success metrics.

When you think about it, it makes intuitive sense. We all know a martyr who goes out of their way to help others and yet fails to meet their own needs or ends up exploited by Takers. We also all know someone everyone loves because they are so helpful, and they succeed because everyone appreciates and feels indebted to them.

While some of those studies say the social stress of being a powerless nice guy can give you a heart attack, the big-picture research shows that the old maxim “The good die young” isn’t true. The Terman Study, which followed many subjects across their entire lives, found that people who were kind actually lived longer, not shorter. You might be inclined to think that getting help from others would prolong your life, but the study showed the reverse: those who gave more to others lived longer.

In a lot of short-term scenarios a little cheating and bullying can pay off. But over time it pollutes the social environment and soon everyone is second-guessing everybody and no one wants to work toward the common good.

Here’s the crazy thing: TFT never got a higher score than its counterpart did in any single game. It never won. But the gains it made in the aggregate were better than those achieved by “winners” who edged out meager profits across many sessions. Axelrod explains this by saying, “Tit for tat won the tournament not by beating the other player but by eliciting behavior from the other player [that] allowed both to do well.” Don’t worry how well the other side is doing; worry about how well you’re doing.

…how to be ethical and successful—but not a chump.

When you take a job take a long look at the people you’re going to be working with—because the odds are you’re going to become like them; they are not going to become like you. You can’t change them. If it doesn’t fit who you are, it’s not going to work.

Chapter 3: Do Quitters Never Win and Winners Never Quit?

All of this raises really important questions: How the heck does an illegal migrant farm worker from a dirt-poor upbringing in the middle of nowhere become one of the greatest brain surgeons in the world? How does he stick with it through all the hard work, suffering, discrimination, and setbacks— when he doesn’t even speak the native language? How does he do this when most of us can’t seem to stick to a diet for more than four days or hit the gym more than annually?

And it’s not all dollars and cents either. Angela Duckworth’s research at the University of Pennsylvania shows that kids with grit are happier, physically healthier, and more popular with their peers. “The capacity to continue trying despite repeated setbacks was associated with a more optimistic outlook on life in 31 percent of people studied, and with greater life satisfaction in 42 percent of them.”

Let’s start with reason number one: where does grit really come from? The answer is often stories. You don’t need to grow up in a poor town in Mexico . . . but you may need a Kalimán comic book. Sound crazy?

If you went out on your lawn and tried to fly like Superman and every time you ended up facedown in the flower bed, it wouldn’t be very long before you wisely concluded you and the Man of Steel have one less thing in common and instead took your car to the grocery store. I can’t do it.

This is often more insidious and less obvious in daily life. We give up, rationalize, accept our fate . . . but then occasionally wonder why we didn’t do better or do more. But we’re not always right that we “can’t do it.” Sometimes there’s a way out that we didn’t see because we gave up.

And it’s only reasonable that these people end up either (1) utterly delusional or (2) far more successful than you or I.

What Viktor Frankl realized was that in the most awful place on Earth, the people who kept going despite the horrors were the ones who had meaning in their lives:

A man who becomes conscious of the responsibility he bears toward a human being who affectionately waits for him, or to an unfinished work, will never be able to throw away his life. He knows the “why” for his existence, and will be able to bear almost any “how.”

Researcher John Gottman realized that just hearing how the couple told the tale of their relationship together predicted with 94 percent accuracy whether or not they’d get divorced.

This is true even in the most profound and distressing examples of sadness: suicides. Roy Baumeister, a professor at Florida State University, found that people who committed suicide often weren’t in the worst circumstances, but they had fallen short of the expectations they had of themselves. Their lives were not matching the stories in their heads. Just as Frankl saw in Auschwitz, the stories determined who would keep going and who would make a run for the wire.

One study showed that we feel meaning in life when we think that we know ourselves. The key word there is “think.” Truly knowing oneself didn’t produce meaning but feeling one did created the results. The story doesn’t need to be accurate to be effective. That’s a little unnerving and maybe even depressing, right?

Fate is that thing we cannot avoid. It comes for us despite how we try to run from it. Destiny, on the other hand, is the thing we must chase, what we must bring to fruition. It’s what we strive toward and make true. When bad things happen, the idea of fate makes us feel better, whereas taking the time to consider eulogy values helps us think more about destiny. Success doesn’t come from shrugging off the bad as unchangeable and saying things are already “meant to be”; it’s the result of chasing the good and writing our own future. Less fate, more destiny.

Vonnegut’s moral is that “We are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful about what we pretend to be.”

A professor at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute redesigned his class to resemble World of Warcraft, and students

studied harder, were more engaged, and even cheated less.

Which raises questions: Why are games, which can be taxing, frustrating, and an awful lot like work, so much fun while our jobs, well . . . suck? Why do kids hate homework that’s repetitive and incredibly hard but they’ll gleefully run away from homework to play games . . . which are repetitive and incredibly hard? Why are puzzles fun but doing your taxes is awful? What is it that makes something a game and not just a frustrating pain in the ass?

Some research has shown that willpower is like a muscle, and it gets tired with overuse. But it only gets depleted if there’s a struggle. Games change the struggle to something else. They make the process fun, and as Mischel showed in his research, we are able to persist far longer and without the same level of teeth-gritting willpower depletion.

Here’s an example: What if I put a big ol’ pile of cocaine in front of you? (I’ll assume, for the sake of argument, you are not a cocaine addict.) Cocaine is pleasurable. You know that. People do it for a reason, right? But you’d likely reply, “No, thanks.” Why? Because it doesn’t jibe with your story. You just don’t see yourself as the kind of person who does cocaine. You could come up with all kinds of reasons why. (What’s a reason? A story.) Would you have to close your eyes and clench your fists and beg me to take the cocaine away? Probably not. You’d exert no willpower on this one. But would the same be true with a juicy steak? Especially if you were hungry? Say you are the kind of person who indulges in steak. Now what happens? Struggle. Willpower depletion. Unless you are a vegetarian. Boom—another story. You’d say no and exert zero willpower. You’d have no trouble ignoring the steak. Change the story and you change your behavior. Games are another kind of story: a fun one.

You’ve just learned what all good games have in common: WNGF. They’re Winnable. They have Novel challenges and Goals, and provide Feedback.

Roughly four times out of five, gamers don’t complete the mission, run out of time, don’t solve the puzzle, lose the fight, fail to improve their score, crash and burn, or die. Which makes you wonder: do gamers actually enjoy failing? As it turns out, yes . . . When we’re playing a well designed game, failure doesn’t disappoint us. It makes us happy in a very particular way: excited, interested, and most of all optimistic.

Now, what if your boss hates you? Or you’re facing discrimination in the workplace? Those games really aren’t winnable. Move on. Find a game you can win.

As Jane McGonigal reports in her book, studies show many C-level executives play computer games at work. Why? “To feel more productive.” Oh, the irony.

Making work a game is quite simple; you don’t have to change what you’re doing all that much, you just have to change your perspective. But therein lies the reason many of us don’t do it: it feels kinda silly.

As Henry David Thoreau said, “The price of anything is the amount of life you exchange for it.”

Research shows that when we choose to quit pursuing unattainable goals, we’re happier, less stressed, and get sick less often. Which people are the most stressed out? Those who wouldn’t quit what wasn’t working.

We rationalize our failures, but we can’t rationalize away the stuff we never tried at all. As we get older we also tend to remember the good things and forget the bad. So simply doing more means greater happiness when we’re older (and cooler stories for the grandkids).

Comedians need to see what fails so they can cut it. They need to know what to “quit.” When comedians can’t fail, they can’t succeed. Here’s Chris Rock again: “Comedians need a place where we can work on that stuff . . . No comedian’s ever done a joke that bombs all the time and kept doing it. Nobody in the history of stand-up. Not one guy.”

The answer is simple: If you don’t know what to be gritty at yet, you need to try lots of things— knowing you’ll quit most of them—to find the answer. Once you discover your focus, devote 5 to 10 percent of your time to little experiments to make sure you keep learning and growing.

YouTube started out as a dating site, of all things. eBay was originally focused on selling PEZ dispensers. Google began as a project to organize library book searches.

It turns out that your brain isn’t very good at telling fantasy from reality. (This is why movies are so thrilling.) When you dream, that grey matter feels you already have what you want and so it doesn’t marshal the resources you need to motivate yourself and achieve. Instead, it relaxes. And you do less, you accomplish less, and those dreams stay mere dreams. Positive thinking, by itself, doesn’t work.

In one study, Peter Gollwitzer and Veronika Brandstätter found that just planning out some basics, like when to do something, where, and how, made students almost 40 percent more likely to follow through with goals.

Chapter 4: It’s Not What You Know, It’s Who You Know (Unless It Really Is What You Know)

He was certainly successful. Erdös produced more papers during his life than any other mathematician—ever. Some were even published posthumously, meaning Erdös, technically, kept publishing seven years after his death. He received at least fifteen honorary doctorates.

On one occasion, Erdös met a mathematician and asked him where he was from. “Vancouver,” the mathematician replied. “Oh, then you must know my good friend Elliot Mendelson,” Erdös said. The reply was “I am your good friend Elliot Mendelson.”

The Fields Medal is the highest honor a mathematician can receive. Paul Erdös never won it. But a number of the people he helped did, and that leads us to what Erdös is best known for: the “Erdös number.” No, it was not a theorem or a mathematical tool. It was simply a measure of how close you were to working with Paul Erdös. (Think of it like Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon—but for nerds.) If you collaborated with Erdös on a paper, you had an Erdös number of one. If you collaborated with someone who collaborated with Erdös, your Erdös number was two, and so on. Paul Erdös was so influential and helped so many people that mathematicians rank themselves by how close they were to working with him.

When you think athlete you might envision the popular captain of the football team in high school. Or maybe the charismatic baseball player telling you to buy razors in that commercial. It’s only natural to think they’re all hard-partying extroverts. You couldn’t be more wrong. Author (and Olympic gold medalist) David Hemery reports that almost nine out of ten top athletes identify as introverts. “A remarkably distinguishing feature is that a large proportion, 89 percent of these sports achievers, classed themselves as introverts . . . Only 6 percent of the sports achievers felt that they were extroverts and the remaining 5 percent felt that they were ‘middle of the road.’”

We’ve established the payoff to networking is huge. But it can feel sleazy. Research from Francesca Gino shows that when we try to meet someone just to get something from them, it makes us feel immoral. The people who feel least sleazy about networking are powerful people. But those who need to network the most—the least powerful—are the most likely to feel bad about it. We like networking better when it’s serendipitous, when it feels like an accident, not deliberate and Machiavellian.

Bestselling author Ramit Sethi told me: We all have friends who are just cool to be around. They’re always sending you awesome stuff. “Hey, check out this book,” “Oh, you’ve got to see this video I just watched. Here, here’s a copy.” That is actually networking, because they’re serving you first. Now, one day if they came to you and said, “Hey man, I know you have a friend who works at X company. I’m actually trying to get connected there. Do you think you can introduce me?” Of course you would say yes. Networking is about a personal relationship.

So if slimy networking is like the mistrustful situation we saw in Moldova, what’s the opposite? Iceland.

FBI behavioral expert Robin Dreeke said the most important thing to do is to “seek someone else’s thoughts and opinions without judging them.” Stop thinking about what you’re going to say next and focus on what they’re saying right now.

Gerard Roche surveyed 1,250 top executives and found two-thirds had had a mentor, and those who did, made more money and were happier with their careers: “The average increase in salary of executives who have had a mentor is 28.8 percent, combined with an average 65.9 percent increase in bonus, for an overall 29.0 percent rise in total cash compensation.” And, ladies, this is even more important for you. Every single one of the successful female executives in the study turned out to have had a mentor.

And once they do get to know you, that research pays off, because it’s very good for you if they think you’re smarter than the average bear. Robert Rosenthal and Lenore Jacobson did a classic study in which teachers were told that certain students were “academic spurters” and had very high potential. At the end of the school year, those kids were tested and had gained an average of 22 IQ points. Here’s the kicker: the “academic spurters” were chosen at random. They weren’t special. But the teacher believing they were special made it a self-fulfilling prophecy. The teachers didn’t spend more time with these kids. Rosenthal “thinks the teachers were more excited about teaching these students.

Atul Gawande is an endocrine surgeon. And a professor at Harvard Medical School. And a staff writer for the New Yorker. And he’s written four bestselling books. And he won a Rhodes Scholarship and a MacArthur “Genius” Grant. And he’s married with three kids. (Every time I look at his résumé I think, Jeez, and what the heck have I been doing with my time?) So in 2011, what did he think the next thing he absolutely needed to do was? Get a coach. Someone who could make him better.

Mentoring a young person is four times more predictive of happiness than your health or how much money you make. So if you’ve got the skills, don’t just think about who can help you. Think about whom you can help.

Resolving difficult conversations means we need less Moldova and more Iceland.

Tim Kreider got stabbed in the throat while on vacation. The knife sunk in two millimeters from his carotid artery, which he describes as the difference between being “flown home in the cargo hold instead of in coach.” He lived. And for the next year nothing could upset him. He just felt so lucky to be alive. Being stabbed in the throat turned the volume down on everything negative. “That’s supposed to bother me? I’ve been stabbed in the throat!” Then hedonic adaptation set in. He found himself getting frustrated by little things again—traffic,

computer problems. Once again, he took being alive for granted. Just like we all do. Tim then came up with a little solution. He makes sure to celebrate his “stabbiversary” every year, to remind himself how lucky he is. And that’s what you need to do. Making time to feel gratitude for what you have undoes the “hedonic adaptation.” And what’s the best way to do this? Thank the people around you. Relationships are the key to happiness, and taking the time to say “thanks” renews that feeling of being blessed.

Chapter 5: Believe In Yourself…Sometimes

Normally Kasparov could look into the eyes of his opponent and try to read him. Is he bluffing? But Deep Blue never flinched. Deep Blue wasn’t even capable of flinching. It shook Kasparov’s confidence all the same. Sometimes the mere appearance of confidence can be the difference between winning and losing.

In a positive way, successful people are “delusional.” They tend to see their previous history as a validation of who they are and what they have done. This positive interpretation of the past leads to increased optimism towards the future and increases the likelihood of future success.

People who believe they can succeed see opportunities, where others see threats. They are not afraid of uncertainty or ambiguity, they embrace it. They take more risks and achieve greater returns. Given the choice, they bet on themselves. Successful people have a high “internal locus of control.” In other words, they do not feel like victims of fate. They see their success as a function of their own motivation and ability—not luck, random chance, or fate. They carry this belief even when luck does play a crucial role in success.

Many studies show faking it also has positive effects on you. In Richard Wiseman’s book The As If Principle, he details a significant amount of research showing that smiling when you’re sad can make you feel happy, and moving like you’re powerful actually makes you more resistant to pain. Other studies show that a feeling of control reduces stress—even if you’re not in control. The perception is all that matters.

Warren Buffett once said, “The CEO who misleads others in public may eventually mislead himself in private.” And there’s good reason to believe he’s right.

As Nathaniel Hawthorne once wrote, “No man, for any considerable period, can wear one face to himself, and another to the multitude, without finally getting bewildered as to which may be the true.”

We all spend a lot of time complaining about incompetence, but as Malcolm Gladwell pointed out in a talk he gave at High Point University, overconfidence is the far bigger problem. Why? Incompetence is a problem that inexperienced people have, and all things being equal, we don’t entrust inexperienced people with all that much power or authority. Overconfidence is usually the mistake of experts, and we do give them a lot of power and authority. Plain and simple, incompetence is frustrating, but the people guilty of it usually can’t screw things up that bad. The people guilty of overconfidence can do much more damage.

Lower self-confidence reduces not only the chances of coming across as arrogant but also of being deluded. Indeed, people with low self-confidence are more likely to admit their mistakes—instead of blaming others—and rarely take credit for others’ accomplishments. This is arguably the most important benefit of low self-confidence because it points to the fact that low self-confidence can bring success, not just to individuals but also to organizations and society.

A study aptly titled “Power, Competitiveness, and Advice Taking: Why the Powerful Don’t Listen” showed that just making someone feel powerful was enough to make them ignore advice from not only novices but also experts in a field.

James Baldwin once wrote, “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

Doctors are known for being on the arrogant side. When a hospital decided it wanted to reduce infections among patients, they insisted that all physicians follow a checklist before procedures. This was a little demeaning, but the administration was serious—so serious that they gave authority to nurses to intervene (with political cover from the top brass) if doctors didn’t follow every step. The results? “The ten-day line-infection rate went from 11 percent to zero.”

Low self-confidence may turn you into a pessimist, but when pessimism teams-up with ambition it often produces outstanding performance. To be the very best at anything, you will need to be your harshest critic, and that is almost impossible when your starting point is high self-confidence.

It was depressed people who saw the world more accurately. Research shows that pessimistic entrepreneurs are more successful, optimistic gamblers lose more money, and the best lawyers are pessimists.

The risk-taking, novelty-seeking, and obsessive personality traits often found in addicts can be harnessed to make them very effective in the workplace. For many leaders, it’s not the case that they succeed in spite of their addiction; rather, the same brain wiring and chemistry that make them addicts also confer on them behavioral traits that serve them well.

This leads to hubris and narcissism. When you check the numbers, there is a solid correlation between self-esteem and narcissism, while the connection between self compassion and narcissism is pretty much zero.

“Self-esteem is the greatest sickness known to man or woman because it’s conditional.” People with self-compassion don’t feel the need to constantly prove themselves, and research shows they are less likely to feel like a “loser.”

Confidence is a result of success, not a cause. So in spite of my fevered recommendation of self compassion, if you still want to focus on confidence, the surest path is to become really good at what you do.

You can become more confident over time with hard work. As Alfred Binet, inventor of the IQ test, said about intelligence, “It is not always the people who start out the smartest who end up the smartest.”

Chapter 6: Work, Work, Work… or Work-Life Balance?

Williams even visited MIT to learn more about the physics of baseball. He studied the best batters and would eventually write a book, The Science of Hitting, that to this day is still considered the best book on the subject.

I figure out what they’re going to throw,” he said. People would marvel at how he could recount the habits and preferences of different pitchers decades after his career came to a close. But this perfectionist sensitivity that made him perform so well led to much strife with sportswriters who covered him. Their criticism enraged a man who already put so much pressure on himself to be the best.

While most professional sports are undeniably a young man’s game, Williams competed in the major leagues until the age of forty-two. During his final year in the pros his home-run percentage was the best of his career, a stellar 9.4. He even hit a home run during his final at bat before retirement in 1960.

In 1999, The Sporting News put him as eighth on their list of best 100 Greatest Baseball Players. He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by George H. W. Bush in 1991. Ted Williams was great because he never stopped working.

Success is not for the lazy, procrastinating, or mercurial.” (Does that mean it’s a good thing that I’m writing these lines at 3:25 A.M.?)

The only place where success comes before work is a dictionary.” Yes, to be the very best you must be a little nuts in the effort department.

“The top 10 percent of workers produce 80 percent more than the average, and 700 percent more than the bottom 10 percent.”

Some people do insane amounts of work and see nothing from it. By the time of his death, Robert Shields had produced a diary that was 37.5 million words long. He spent four hours a day recording everything from his blood pressure to the junk mail he received. He even woke up every two hours so he could detail his dreams. This didn’t make him rich and didn’t even garner him a Guinness Book of World Records listing. It just made him a crazy man with one of the most morbidly fascinating obituaries ever.

Hours alone also aren’t enough. Those hours need to be hard. You need to be pushing yourself to be better, like Ted Williams. You’ve spent a lot of hours in your life driving, right? Are you ready to compete in NASCAR or Formula 1? Probably not.

As Michelangelo once said, “If people knew how hard I worked to achieve my mastery, it wouldn’t seem so wonderful after all.”

If a meaningful career boosts longevity, what kills you sooner? Unemployment. Eran Shor, a professor at McGill University, found that being jobless increases premature mortality by a whopping 63 percent. And preexisting health issues made no difference, implying that it’s not a correlation, it’s very likely causation. This was no small study. It covered forty years, twenty million people, and fifteen countries. That 63 percent figure held no matter where the person lived.

What about retirement? That’s the “good” unemployment, right? Wrong. Retiring is associated with cognitive decline, heart disease, and cancer. Those effects weren’t due to aging but because people stop being active and engaged.

Remember how I said that working too hard was one of the biggest regrets people had on their deathbed? Definitely true. But what was the number-one regret? “I wish I’d had the courage to live a life true to myself, not the life others expected of me.”

Albert Einstein and Charlie Chaplin attended the premiere of City Lights together. The crowd went wild for the two superstars, and Chaplin said to the great scientist, “They cheer me because they all understand me, and they cheer you because no one understands you.”

While he was an attentive father when his boys were young, as the years passed Einstein would spend more and more time in his head. After his divorce, he saw his children rarely, focusing more on his work. His son Eduard struggled with mental illness and attempted suicide, eventually dying in a psychiatric hospital. Einstein had not visited him for more than three decades. His other son, Hans Albert, is quoted as saying, “Probably the only project he ever gave up on was me.” Hard work creates talent. And talent plus time creates success . . . but how much is too much?

Williams divorced three times. One woman he dated, Evelyn Turner, repeatedly refused his marriage proposals. She said she would be his wife only if he assured her she would come first in his life. Ted responded, “It’s baseball first, fishing second, and you third.” When he fought with wife number three, Dolores Wettach, she threatened to write a sequel to Williams’s biography titled My Turn at Bat Was No Ball.

When his daughter Bobby-Jo would ask him about his childhood, he told her to read his autobiography.

As George Bernard Shaw said, “The true artist will let his wife starve, his children go barefoot, his mother drudge for his living at seventy, sooner than work at anything but his art.” And where was Mozart when his wife was giving birth to their first child? In the other room composing, of course.

That’s also why passionate people may destroy their relationships or physically pass out from exhaustion but not burn out the frazzled way the average worker might. Researchers Cary Cherniss and David Kranz found that burnout was “virtually absent in monasteries, Montessori schools, and religious care centers where people consider their work as a calling rather than merely a job.”

A study from the Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies found that “workplace fun was a stronger predictor of applicant attraction than compensation and opportunities for advancement.” Yeah, that means exactly what you think: money and promotions weren’t nearly as important to people as working somewhere

fun.

In fact, you’re engaging in your prime creative time long before you get to the office. Most people come up with their best ideas in the shower. Scott Barry Kaufman of the University of Pennsylvania found that 72 percent of people have new ideas in the shower, which is far more often than when they’re at work. Why are showers so powerful? They’re relaxing. Remember, Archimedes didn’t have his “Eureka” moment at the office. He was enjoying a nice warm bath at the time.

TV shows you twenty-something Silicon Valley billionaires. Think you’re good at something? There’s someone on the Internet who is better, works less, and is happier. They have nice teeth too. For most of human existence when we looked around us there were one or two hundred people in our tribe and we could be the best at something. We could stand out and be special and valuable. Now our context is a global tribe of seven-plus billion. There’s always someone better to compare yourself to, and the media is always reporting on these people, which raises the standards just when you think you may be close to reaching them.

Barry Schwartz says that what we often fail to realize is those constraints are welcome. They make decisions easier. They make life simpler. They make it “not your fault.” So they make us happier. We believe these constraints are ultimately worth the trade-off. Limitless freedom is alternately paralyzing and overwhelming. Plus, the only place we get good limits these days is when we determine them ourselves, based on our values.

How did an illiterate young man in a horrible place during a horrible time conquer more territory in twenty-five years than the Romans did in four hundred? How did he build an empire that spanned over twelve million contiguous miles? And do it with an army that never grew larger than a hundred thousand men, which, as author Jack Weatherford explains, is “a group that could comfortably fit into the larger sports stadiums of the modern era”?

He was a fatherless, illiterate nobody from a terrible place at a terrible time but became one of the most powerful men to ever live. Genghis Khan did not blindly react to problems. He thought about what he wanted. He made plans. And then he imposed his will on the world.

Georgetown University professor Cal Newport is the Genghis Khan of productivity. And Cal thinks to-do lists are the devil’s work.

Shallow work stops you from getting fired—but deep work is what gets you promoted.

We got to the moon and built the pyramids without email and Facebook. You can go a couple of hours without checking them.

One of the big lessons from social science in the last forty years is that environment matters. If you go to a buffet and the buffet is organized in one way, you will eat one thing. If it’s organized in a different way, you’ll eat different things. We think that we make decisions on our own, but the environment influences us to a great degree. Because of that we need to think about how to change our environment.

Ariely told me of a simple study done at Google’s New York office. Instead of putting M&M’s out in the open, they put them in containers. No big deal. What was the result? People ate three million fewer of them in a single month. So close that web browser. Charge your phone on the other side of the room.

Currently on this planet, 0.5 percent of all men are one of Genghis Khan’s descendants. That’s one in two hundred. So by, um, many standards, he was successful. He had a plan. You don’t need to conquer the world, literally or metaphorically. “Good enough” is good enough if you keep the big four in mind.

Conclusion: What Makes A Successful Life?

Success is strange in that it cultivates more success. Once I had achieved something it encouraged me to try even harder. It expanded my perception of what was possible. If I could do this, then what else could I do?

“After forty years of intensive research on school learning in the United States as well as abroad, my major conclusion is: What any person in the world can learn, almost all persons can learn, if provided with the appropriate prior and current conditions of learning.”

What’s the most important thing to remember when it comes to success?

One word: alignment.

Success is not the result of any single quality; it’s about alignment between who you are and where you choose to be. The right skill in the right role. A good person surrounded by other good people. A story that connects you with the world in a way that keeps you going. A network that helps you, and a job that leverages your natural introversion or extroversion. A level of confidence that keeps you going while learning and forgiving yourself for the inevitable failures. A balance between the big four that creates a well-rounded life with no regrets.

The Sedona Illuminati: James Clear, Josh Kaufman, Steve Kamb, Ryan Holiday Shane Parrish, Nir Eyal, and Tim Urban. The lovely people who supported my semi-insane endeavors: Bob Radin, Paulo Coelho, Chris Yeh, Jennifer Aaker, and Detective Jeff Thompson (who asked me if I’d like to come train with the NYPD Hostage Negotiation Team—like I’m gonna say no to that.)

And to my girlfriend junior year in college who laughed in my face when I said I wanted to be a writer. Thanks for the motivation.

Book Review (Personal Opinion):

I’ve read a bunch of business books that say are based on science. But Barker’s book blows all of them away. First of all, he presented the views in a remarkable way by providing us with the case for both sides of the medal. He promises that at the start of his books and he delivers! The examples are fascinating and his writing style is so humorous that it makes Barking Up The Wrong Tree a true page-turner!

Rating: 9/10

This Book Is For (Recommend):

- A millennial stuck with only one way of achieving success— courtesy of a self-help guru

- A young professional looking for a balanced way of achieving success

- An entrepreneur who wants to become successful without knowing how to do it

If You Want To Learn More

Here’s Eric Barker talking about Barking Up The Wrong Tree at Google.

Google Talks

How I’ve Implemented The Ideas From The Book

There’s so much that I got from this book. First of all, I realized both sides of the aisle for the presented views of success and picked the ones that match my context and reality. For my business success, it was mostly about knowing what to do instead of who I know so I focused my efforts on the latter. Also, I realized why it’s a good thing that I’m not super successful in an area where I wanted to be— that requires a certain type of personality and I’m glad I’m not on that path.

One Small Actionable Step You Can Do

I’ll put forth a couple of small actionable steps:

- Find an environment where your otherwise negative trait, becomes a positive amplifier (an “intensifier”)

- Find a Giver and Give something of value to them

- Start a hobby

- Quit something that makes you miserable

- Ask a person you admire for lunch/coffee

- Stay at home for the weekend and start learning a new skill

- Launch something to the eye of the public that is still not perfect