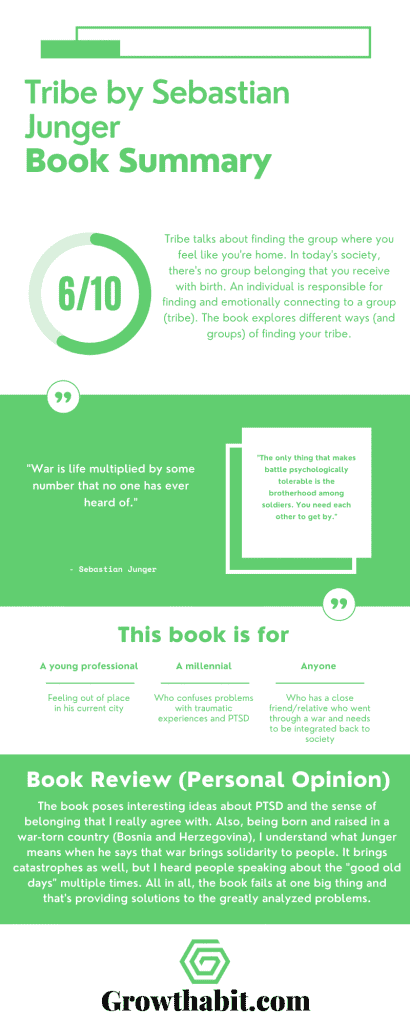

Tribe talks about finding the group where you feel like you’re home. In today’s society, there’s no group belonging that you receive with birth. An individual is responsible for finding and emotionally connecting to a group (tribe). The book explores different ways (and groups) of finding your tribe.

Book Title: Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging

Author: Sebastian Junger

Date of Reading: September 2018

Rating: 6/10

What Is Being Said In Detail:

Tribe is divided into four chapters:

- The Men And The Dogs

- War Makes You An Animal

- In Bitter Safety I Awake

- Calling Home From Mars

“The Men And The Dogs” talks about the indigenous American tribes and Western society. A lot of individuals from the industrialized society fled that way of life to live with indigenous people.

They sought the feeling of community, connectedness, and purpose. It was something they couldn’t find in the industrial society. A lot of people fled to the tribes, but only a handful of people from the indigenous tribes left to join the Western society.

“War Makes You An Animal” talks about the lack of necessity in today’s society to test people’s loyalty to the common good. Life is just too safe and predictable and people almost never need to “prove their worth.”

A war situation is different and you need to rely on your neighbor and he needs to rely on you. Paradoxically, people start to become more united, loved, and connected during the hardships because they need to rely on each other with their lives.

Stories from Bosnia and Herzegovina and London Blitzes provide examples for this statement.

“In Bitter Safety I Awake” talks about PTSD. Junger finds out that PTSD isn’t actually caused by trauma received on the battlefield, but by loneliness and lack of integration when the person comes back to society.

Social isolation is a problem for many soldiers who come back from the battlefield, exchanging the strong bonds they had with their platoons for weak ties with people in the safe society.

This is why some soldiers want to get back to the battlefield— they want to feel that level of trust, unity, and connectedness they had with their troops.

“Calling Home From Mars” talks about the disconnection in American society between the military and people. Also, Junger talks about the problems of school shootings, a phenomenon that occurs mostly in affluent, white, low-crime, Christian suburbs.

Junger argues that this happens because of social isolation and disconnection from the group/tribe. He calls for ceremonies that could help people regain some social solidarity and cohesion.

Most Important Keywords, Sentences, Quotes:

Introduction

“In the fall of 1986, just out of college, I set out to hitchhike across the northwestern part of the United States.”

“The sheer predictability of life in an American suburb left me hoping—somewhat irresponsibly —for a hurricane or a tornado or something that would require us to all band together to survive.

Something that would make us feel like a tribe. What I wanted wasn’t destruction and mayhem but the opposite: solidarity.”

“How do you become an adult in a society that doesn’t ask for sacrifice? How do you become a man in a world that doesn’t require courage?”

“The word “tribe” is far harder to define, but a start might be the people you feel compelled to share the last of your food with.”

“This book is about why that sentiment is such a rare and precious thing in modern society, and how the lack of it has affected us all. It’s about what we can learn from tribal societies about loyalty and belonging and the eternal human quest for meaning.

It’s about why—for many people—war feels better than peace and hardship can turn out to be a great blessing and disasters are sometimes remembered more fondly than weddings or tropical vacations.

Humans don’t mind hardship, in fact they thrive on it; what they mind is not feeling necessary. Modern society has perfected the art of making people not feel necessary. It’s time for that to end.”

The Men And The Dogs

“Individual authority was earned rather than seized and imposed only on people who were willing to accept it. Anyone who didn’t like it was free to move somewhere else.”

“By the end of the nineteenth century, factories were being built in Chicago and slums were taking root in New York while Indians fought with spears and tomahawks a thousand miles away. It may say something about human nature that a surprising number of Americans—mostly men—wound up joining Indian society rather than staying in their own.

They emulated Indians, married them, were adopted by them, and on some occasions even fought alongside them. And the opposite almost never happened: Indians almost never ran away to join white society.

Emigration always seemed to go from the civilized to the tribal, and it left Western thinkers flummoxed about how to explain such an apparent rejection of their society.”

“On the other hand, Franklin continued, white captives who were liberated from the Indians were almost impossible to keep at home.“

”Thousands of Europeans are Indians, and we have no examples of even one of those Aborigines having from choice become European,” a French émigré named Hector de Crèvecoeur lamented in 1782.

“There must be in their social bond something singularly captivating and far superior to anything to be boasted of among us.”

“Personal property was usually limited to whatever could be transported by horse or on foot, so gross inequalities of wealth were difficult to accumulate. Successful hunters and warriors could support multiple wives, but unlike modern society, those advantages were generally not passed on through the generations.

Social status came through hunting and war, which all men had access to, and women had far more autonomy and sexual freedom—and bore fewer children—than women in white society.”

“Because of these basic freedoms, tribal members tended to be exceedingly loyal.

A white captive of the Kickapoo Nation who came to be known as John Dunn Hunter wrote that he had never heard of even a single instance of treason against the tribe, and as a result, punishments for such transgressions simply didn’t exist.

But cowardice was punished by death, as was murder within the tribe or any kind of communication with the enemy.

It was a simple ethos that promoted loyalty and courage over all other virtues and considered the preservation of the tribe an almost sacred task. Which indeed it was.”

“The relatively relaxed pace of Kung life—even during times of adversity—challenged long-standing ideas that modern society created a surplus of leisure time.

It created exactly the opposite: a desperate cycle of work, financial obligation, and more work. The Kung had far fewer belongings than Westerners, but their lives were under much greater personal control.”

“And as society modernized, people found themselves able to live independently from any communal group.

A person living in a modern city or a suburb can, for the first time in history, go through an entire day—or an entire life—mostly encountering complete strangers. They can be surrounded by others and yet feel deeply, dangerously alone.”

“This stands in stark contrast to many modern societies, where the suicide rate is as high as 25 cases per 100,000 people. (In the United States, white middle-aged men currently have the highest rate at nearly 30 suicides per 100,000.)”

“The mechanism seems simple: poor people are forced to share their time and resources more than wealthy people are, and as a result they live in closer communities.

Inter-reliant poverty comes with its own stresses—and certainly isn’t the American ideal—but it’s much closer to our evolutionary heritage than affluence.”

“In fact, public defenders, who have far lower status than corporate lawyers, seem to lead significantly happier lives.

The findings are in keeping with something called self-determination theory, which holds that human beings need three basic things in order to be content: they need to feel competent at what they do; they need to feel authentic in their lives, and they need to feel connected to others.”

“What tribal people would consider a profound betrayal of the group, modern society simply dismisses it as fraud.

Around 3 percent of people on unemployment assistance intentionally cheat the system, for example, which costs the United States more than $2 billion a year. Such abuse would be immediately punished in tribal society.”

“Cowardice is another form of community betrayal, and most Indian tribes punished it with immediate death. (If that seems harsh, consider that the British military took “cowards” off the battlefield and executed them by firing squad as late as World War I.)”

“United States Securities and Exchange Commission has been trying to force senior corporate executives to disclose the ratio of their pay to that of their median employees.”

“Paine acknowledged that these tribes lacked the advantages of the arts and science and manufacturing, and yet they lived in a society where personal poverty was unknown and the natural rights of man were actively promoted.”

War Makes You An Animal

”You don’t owe your country nothing,” I remember him telling me. “You owe it something, and depending on what happens, you might owe it your life.”

“To the extent that boys are drawn to war, it may be less out of an interest in violence than a longing for the kind of maturity and respect that often come with it.”

“That was how I came to understand why I found myself, broke and directionless, on the tarmac of the Sarajevo airport at age thirty-one, listening to the tapping of machine-gun fire in a nearby suburb named Dobrinja”

“Over the course of the three-year siege almost 70,000 people were killed or wounded by Serb forces shooting into the city—roughly 20 percent of the population.”

”An earthquake achieves what the law promises but does not in practice maintain,” one of the survivors wrote. “The equality of all men.”

“(Despite erroneous news reports, New Orleans experienced a drop in crime rates after Hurricane Katrina, and much of the “looting” turned out to be people looking for food.)”

”Ten thousand people had come together without ties of friendship or economics, with no plans at all as to what they meant to do,” one man wrote about life in a massive concrete structure known as Tilbury Shelter.

“They found themselves, literally overnight, inhabitants of a vague twilight town of strangers. At first there were no rules, rewards or penalties, no hierarchy or command.

Almost immediately, ‘laws’ began to emerge—laws enforced not by police and wardens (who at first proved helpless in the face of such multitudes) but by the shelterers themselves.”

“Great sociologist Emile Durkheim, who found that when European countries went to war, suicide rates dropped.”

“An Irish psychologist named H. A. Lyons found that suicide rates in Belfast dropped 50 percent during the riots of 1969 and 1970, and homicide and other violent crimes also went down.”

“County Derry, on the other hand—which suffered almost no violence at all—saw male depression rates rise rather than fall. Lyons hypothesized that men in the peaceful areas were depressed because they couldn’t help their society by participating in the struggle.”

”When people are actively engaged in a cause their lives have more purpose… with a resulting improvement in mental health,”

”It would be irresponsible to suggest violence as a means of improving mental health, but the Belfast findings suggest that people will feel better psychologically if they have more involvement with their community.”

“The Blitz, as bad as it was, paled in comparison to what the Allies did. Dresden lost more people in one night than London did during the entire war.

Firestorms engulfed whole neighborhoods and used up so much oxygen that people who were untouched by the blasts reportedly died of asphyxiation instead.”

“The more the Allies bombed, the more defiant the German population became.”

“Fritz went on to complete a more general study of how communities respond to calamity. After the war he turned his attention to natural disasters in the United States and formulated a broad theory about social resilience.

He was unable to find a single instance where communities that had been hit by catastrophic events lapsed into sustained panic, much less anything approaching anarchy.”

“In 1961, Fritz assembled his ideas into a lengthy paper that began with the startling sentence, “Why do large-scale disasters produce such mentally healthy conditions?”

“Disasters, he proposed, create a “community of sufferers” that allows individuals to experience an immensely reassuring connection to others.”

“Fritz found, class differences are temporarily erased, income disparities become irrelevant, race is overlooked, and individuals are assessed simply by what they are willing to do for the group.”

“As soon as relief flights began delivering aid to the area, class divisions returned and the sense of brotherhood disappeared. The modern world had arrived.”

“Men perform the vast majority of bystander rescues, and children, the elderly, and women are the most common recipients of them. Children are helped regardless of gender, as are the elderly, but women of reproductive age are twice as likely to be helped by a stranger than men are.

Men have to wait, on average, until age seventy-five before they can expect the same kind of assistance in a life-threatening situation that women get their whole lives.

Given the disproportionately high value of female reproduction to any society, risking male lives to save female lives makes enormous evolutionary sense.”

“In late 2015, a bus in eastern Kenya was stopped by gunmen from an extremist group named AlShabaab that made a practice of massacring Christians as part of a terrorism campaign against the Western-aligned Kenyan government.

The gunmen demanded that Muslim and Christian passengers separate themselves into two groups so that the Christians could be killed, but the Muslims—most of whom were women—refused to do it.

They told the gunmen that they would all die together if necessary, but that the Christians would not be singled out for execution. The Shabaab eventually let everyone go.”

“The beauty and the tragedy of the modern world is that it eliminates many situations that require people to demonstrate a commitment to the collective good.

Protected by police and fire departments and relieved of most of the challenges of survival, an urban man might go through his entire life without having to come to the aid of someone in danger—or even give up his dinner.

“What would you risk dying for—and for whom— is perhaps the most profound question a person can ask themselves.

The vast majority of people in modern society are able to pass their whole lives without ever having to answer that question, which is both an enormous blessing and a significant loss.”

“Twenty years after the end of the siege of Sarajevo, I returned to find people talking a little sheepishly about how much they longed for those days. More precisely, they longed for who they’d been back then.

Even my taxi driver on the ride from the airport told me that during the war, he’d been in a special unit that slipped through the enemy lines to help other besieged enclaves. “And now look at me,” he said, dismissing the dashboard with a wave of his hand.

”I missed being that close to people, I missed being loved in that way,” she told me. “In Bosnia —as it is now—we don’t trust each other anymore; we became really bad people.

We didn’t learn the lesson of the war, which is how important it is to share everything you have with human beings close to you. The best way to explain it is that the war makes you an animal.

We were animals. It’s insane— but that’s the basic human instinct, to help another human being who is sitting or standing or lying close to you.” I asked Ahmetašević if people had ultimately been happier during the war.

“We were the happiest,” Ahmetašević said. Then she added: “And we laughed more.”

In Bitter Safety I Awake

“What I had was classic short-term PTSD.

From an evolutionary perspective, it’s exactly the response you want to have when your life is in danger: you want to be vigilant, you want to avoid situations where you are not in control, you want to react to strange noises, you want to sleep lightly and wake easily, you want to have flashbacks and nightmares that remind you of specific threats to your life, and you want to be, by turns, angry and depressed.

Anger keeps you ready to fight, and depression keeps you from being too active and putting yourself in more danger.”

“But in addition to all the destruction and loss of life, war also inspires ancient human virtues of courage, loyalty, and selflessness that can be utterly intoxicating to the people who experience them.”

“Because modern society often fights wars far away from the civilian population, soldiers wind up being the only people who have to switch back and forth.

Siegfried Sassoon, who was wounded in World War I, wrote a poem called “Sick Leave” that perfectly described the crippling alienation many soldiers feel at home: “In bitter safety I awake, unfriended,” he wrote. “And while the dawn begins with slashing rain / I think of the Battalion in the mud.”

“A 2011 study of street children in Burundi found the lowest PTSD rates among the most aggressive and violent children.”

“Almost everyone exposed to trauma reacts by having some sort of short-term reaction to it— acute PTSD. That reaction clearly has evolved in mammals to keep them both reactive to danger and out of harm’s way until the threat has passed.

Long-term PTSD, on the other hand—the kind that can last years or even a lifetime—is clearly maladaptive and relatively uncommon. Many studies have shown that in the general population, at most 20 percent of people who have been traumatized get long-term PTSD.”

“Rape is one of the most psychologically devastating things that can happen to a person, for example—far more traumatizing than most military deployments—and according to a 1992 study, close to one hundred percent of rape survivors exhibited extreme trauma immediately afterward.

And yet almost half of rape survivors experienced a significant decline in their trauma symptoms within weeks or months of their assault.”

”For most people in combat, their experiences range from the best of times to the worst of times. It’s the most important thing someone has ever done—especially since these people are so young when they go in—and it’s probably the first time they’ve ever been free, completely, of societal constraints. They’re going to miss being entrenched in this defining world.”

“VA because they worry about losing their temper around patients who they think are milking the system. “It’s the real deals—the guys who have seen the most—that this tends to bother,” he told me.”

“It’s common knowledge in the Peace Corps that as stressful as life in a developing country can be, returning to a modern country can be far harder.

One study found that one in four Peace Corps volunteers reported experiencing significant depression after their return home, and that figure more than doubled for people who had been evacuated from their host country during wartime or some other kind of emergency.”

“We had no hopes of becoming officers. I liked that feeling very much… It was the absence of competition and boundaries and all those phony standards that created the thing I loved about the Army.”

“Adversity often leads people to depend more on one another, and that closeness can produce a kind of nostalgia for the hard times that even civilians are susceptible to.”

“What people miss presumably isn’t danger or loss but the unity that these things often engender.”

“Peace Corps volunteer during the start of the civil war in 2002 and experienced firsthand the extremely close bonds created by hardship and danger.

“We are not good to each other. Our tribalism is to an extremely narrow group of people: our children, our spouse, maybe our parents. Our society is alienating, technical, cold, and mystifying.

Our fundamental desire, as human beings, is to be close to others, and our society does not allow for that.”

“Kohrt told me about those ex-combatants. “PTSD is a disorder of recovery, and if treatment only focuses on identifying symptoms, it pathologizes and alienates vets. But if the focus is on family and community, it puts them in a situation of collective healing.”

“Despite decades of intermittent war, the Israel Defense Forces have by some measures a PTSD rate as low as 1 percent.”

“According to Shalev, the closer the public is to the actual combat, the better the war will be understood and the less difficulty soldiers will have when they come home.”

“The Israelis are benefiting from what the author and ethicist Austin Dacey describes as a “shared public meaning” of the war.”

“Such public meaning is probably not generated by the kinds of formulaic phrases, such as “Thank you for your service,” that many Americans now feel compelled to offer soldiers and vets.

Neither is it generated by honoring vets at sporting events, allowing them to board planes first, or giving them minor discounts at stores. If anything, these token acts only deepen the chasm between the military and civilian populations by highlighting the fact that some people serve their country but the vast majority don’t.

In Israel, where around half of the population serves in the military, reflexively thanking someone for their service makes as little sense as thanking them for paying their taxes. It doesn’t cross anyone’s mind.”

“Because modern society has almost completely eliminated trauma and violence from everyday life, anyone who does suffer those things is deemed to be extraordinarily unfortunate.

This gives people access to sympathy and resources but also creates an identity of victimhood that can delay recovery.”

”In tribal cultures, combat can be part of the maturation process,”

”When youth return from combat, their return is seen as integral to their own society— they don’t feel like outsiders.

In the United States we valorize our vets with words and posters and signs, but we don’t give them what’s really important to Americans, what really sets you apart as someone who is valuable to society—we don’t give them jobs.

All the praise in the world doesn’t mean anything if you’re not recognized by society as someone who can contribute valuable labor.”

“Iroquois warriors who dominated just about every tribe within 500 miles of their home territory would return to a community that still needed them to hunt and fish and participate in the fabric of everyday life.”

“Something called “social resilience” have identified resource sharing and egalitarian wealth distribution as major components of a society’s ability to recover from hardship.

And societies that rank high on social resilience—such as kibbutz settlements in Israel—provide soldiers with a significantly stronger buffer against PTSD than low-resilience societies.

In fact, social resilience is an even better predictor of trauma recovery than the level of resilience of the person himself.”

Calling Home From Mars

“A rampage shooting has never happened in an urban ghetto, for example; in fact, indiscriminate attacks at schools almost always occur in otherwise safe, predominantly white towns.

Around half of rampage killings happen in affluent or upper middle-class communities, and the rest tend to happen in rural towns that are majority-white, Christian, and low-crime.”

“Gang shootings—as indiscriminate as they often are—still don’t have the nihilistic intent of rampages. Rather, they are rooted in an exceedingly strong sense of group loyalty and revenge, and bystanders sometimes get killed in the process.”

“But the spirit of community healing and connection that forms the basis of these ceremonies is one that a modern society might draw on. In all cultures, ceremonies are designed to communicate the experience of one group of people to the wider community.

When people bury loved ones, when they wed, when they graduate from college, the respective ceremonies communicate something essential to the people who are watching.

The Gourd Dance allowed warriors to recount and act out their battlefield exploits to the people they were protecting. If contemporary America doesn’t develop ways to publicly confront the emotional consequences of war, those consequences will continue to burn a hole through the vets themselves.”

“But a community ceremony like that would finally return the experience of war to our entire nation, rather than just leaving it to the people who fought. The bland phrase, “I support the troops,” would then mean showing up at the town hall once a year to hear these people out.”

“Today’s veterans often come home to find that, although they’re willing to die for their country, they’re not sure how to live for it.”

“To make matters worse, politicians occasionally accuse rivals of deliberately trying to harm their own country—a charge so destructive to group unity that most past societies would probably have just punished it as a form of treason.”

“In combat, soldiers all but ignore differences of race, religion, and politics within their platoon. It’s no wonder many of them get so depressed when they come home.”

“Unlike criticism, contempt is particularly toxic because it assumes a moral superiority in the speaker. Contempt is often directed at people who have been excluded from a group or declared unworthy of its benefits.

Contempt is often used by governments to provide rhetorical cover for torture or abuse. Contempt is one of four behaviors that, statistically, can predict divorce in married couples. People who speak with contempt for one another will probably not remain united for long.”

“Joseph Cassano of AIG Financial Products—known as “Mr. Credit-Default Swap”—led a unit that required a $99 billion bailout while simultaneously distributing $1.5 billion in year-end bonuses to his employees—including $34 million to himself.

Robert Rubin of Citibank received a $10 million bonus in 2008 while serving on the board of directors of a company that required $63 billion in federal funds to keep from failing.

Lower down the pay scale, more than 5,000 Wall Street traders received bonuses of $1 million or more despite working for nine of the financial firms that received the most bailout money from the US government.”

“The firm found people for top executive positions around the country, but that didn’t protect it from economic downturns, and in the 1990s, Bauman’s company experienced its first money-losing year in three decades.

According to the Times notice, Mr. Bauman called his employees into a meeting and asked them to accept a 10 percent reduction in salary so that he wouldn’t have to fire anyone. They all agreed.”

“Then he quietly decided to give up his personal salary until his company was back on safe ground. The only reason his staff found out was because the company bookkeeper told them.”

“He clearly understood that belonging to society requires sacrifice, and that sacrifice gives back way more than it costs. (“It was better when it was really bad,” someone spray painted on a wall about the loss of social solidarity in Bosnia after the war ended.”

Postscript

“Suppose, now, not to give them flour, lard,” he explained. “Just dead inside.” There, finally, was my answer for why the homeless guy outside Gillette gave me his lunch thirty years ago: just dead inside. It was the one thing that, poor as he was, he absolutely refused to be.”

Book Review (Personal Opinion):

The book poses interesting ideas about PTSD and the sense of belonging that I really agree with.

Also, being born and raised in a war-torn country (Bosnia and Herzegovina), I understand what Junger means when he says that war brings solidarity to people. It brings catastrophes as well, but I heard people speaking about the “good old days” multiple times.

All in all, the book fails at one big thing and that’s providing solutions to the greatly analyzed problems.

Rating: 6/10

This Book Is For (Recommend):

- A young professional feeling out of place in his current city

- A millennial who confuses problems with traumatic experiences and PTSD

- Anyone who has a close friend/relative who went through a war and needs to be integrated back to society

If You Want To Learn More

Here’s Sebastian Junger talking about Tribe at Google.

Google Talks

How I’ve Implemented The Ideas From The Book

I was born and raised in a war-torn country with parents who survived the war. My father suffers from PTSD and I’ve actually recommended him to read this book.

One Small Actionable Step You Can Do

Find out when you have a town-hall veteran meeting, attend one, listen to their stories, and later talk with them. You will be surprised.