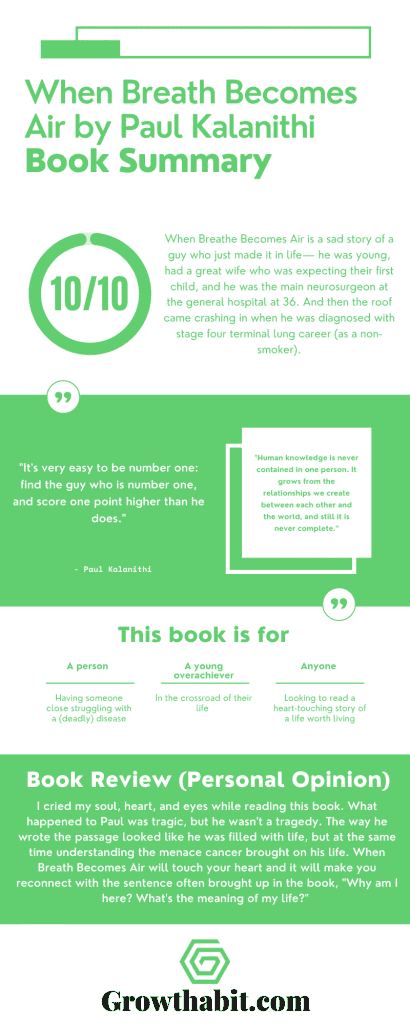

When Breathe Becomes Air is a sad story of a guy who just made it in life— he was young, had a great wife who was expecting their first child, and he was the main neurosurgeon at the general hospital at 36.

And then the roof came crashing in when he was diagnosed with stage four terminal lung career (as a non-smoker).

Book Title: When Breath Becomes Air

Author: Paul Kalanithi

Date of Reading: December 2016

Rating: 10/10

What Is Being Said In Detail:

Damn, this book hit me so hard when I read it. Paul Kalanithi wanted to study English language and literature and you can see that translating into the book. It’s stunning by all means— the descriptions are vivid, the style makes it a page-turner, and the emotions… they hit hard as a truck.

When Breath Becomes Air has a two-part structure. In the first part, Kalanithi describes how his life looked like before finding out that he had stage four lung career. The second part details the years of fighting the sickness and the aftermath of his early death (written by his wife).

Most Important Keywords, Sentences, Quotes:

Prologue

I knew a lot about back pain—its anatomy, its physiology, the different words patients used to describe different kinds of pain—but I didn’t know what it felt like. Maybe that’s all this was. Maybe.

A young nurse, one I hadn’t met, poked her head in. “The doctor will be in soon.” And with that, the future I had imagined, the one just about to be realized, the culmination of decades of striving, evaporated.

PART I – In Perfect Health I Begin

Conrad, for his hypertuned sense of how miscommunication between people can so profoundly impact their lives.

Literature not only illuminated another’s experience, it provided, I believed, the richest material for moral reflection. My brief forays into the formal ethics of analytic philosophy felt dry as a bone, missing the messiness and weight of real human life.

I wasn’t sure where my life was headed. My thesis—“Whitman and the Medicalization of Personality”—was well-received, but it was unorthodox, including as much history of psychiatry and neuroscience as literary criticism. It didn’t quite fit in an English department.

Words began to feel as weightless as the breath that carried them. Stepping back, I realized that I was merely confirming what I already knew: I wanted that direct experience.

It was only in practicing medicine that I could pursue a serious biological philosophy. Moral speculation was puny compared to moral action. I finished my degree and headed back to the States. I was going to Yale for medical school.

It should be noted, entirely reasonable. Indeed, this is how 99 percent of people select their jobs: pay, work environment, hours. But that’s the point. Putting lifestyle first is how you find a job—not a calling.

Because the brain mediates our experience of the world, any neurosurgical problem forces a patient and family, ideally with a doctor as a guide, to answer this question: What makes life meaningful enough to go on living?

Any major illness transforms a patient’s—really, an entire family’s—life. V maintained that our only obligation was to be authentic to the scientific story and to tell it uncompromisingly.

I’d never met someone so successful who was also so committed to goodness. V was an actual paragon.

My clinical duties in the hospital. His hair had thinned and whitened, and the spark in his eyes had dulled.

During our final weekly chat, he turned to me and said, You know, today is the first day it all seems worth it. I mean, obviously, I would’ve gone through anything for my kids, but today is the first day that all the suffering seems worth it.”

How little do doctors understand the hells through which we put patients.

If boredom is, as Heidegger argued, the awareness of time passing, then surgery felt like the opposite: the intense focus made the arms of the clock seem arbitrarily placed. Two hours could feel like a minute.

Onerous yoke, that of mortal responsibility. Our patients’ lives and identities may be in our hands, yet death always wins. Even if you are perfect, the world isn’t.

The secret is to know that the deck is stacked, that you will lose, that your hands or judgment will slip, and yet still struggle to win for your patients. You can’t ever reach perfection, but you can believe in an asymptote toward which you are ceaselessly striving.

PART II – Cease Not till Death

I found myself the sheep, lost and confused. Severe illness wasn’t life-altering, it was life-shattering.

Yes, all cancer patients are unlucky, but there’s cancer, and then there’s CANCER, and you have to be really unlucky to have the latter.

How else did I make life-and-death decisions? Then I recalled the times I had been wrong: the time I had counseled a family to withdraw life support for their son, only for the parents to appear two years later, showing me a YouTube video of him playing piano, and delivering cupcakes in thanks for saving his life.

Like my own patients, I had to face my mortality and try to understand what made my life worth living—and I needed Emma’s help to do so.

Torn between being a doctor and being a patient, delving into medical science and turning back to literature for answers, I struggled, while facing my own death, to rebuild my old life—or perhaps find a new one.

Years ago, it had occurred to me that Darwin and Nietzsche agreed on one thing: the defining characteristic of the organism is striving. Describing life otherwise was like painting a tiger without stripes.

After so many years of living with death, I’d come to understand that the easiest death wasn’t necessarily the best. We talked it over. Our families gave their blessing. We decided to have a child. We would carry on living, instead of dying.

Terms: acquiring rich experiences, then retreating to cogitate and write about them. I needed words to go forward. And so it was literature that brought me back to life during his time.

Completing Samuel Beckett’s seven words, words I had learned long ago as an undergraduate: I’ll go on. I got out of bed and took a step forward, repeating the phrase over and over: “I can’t go on. I’ll go on.”

(People often ask if it is a calling, and my answer is always yes. You can’t see it as a job, because if it’s a job, it’s one of the worst jobs there is.)

But the truth was, it was joyless. The visceral pleasure I’d once found in operating was gone, replaced by an iron focus on overcoming the nausea, the pain, the fatigue.

The tricky part of illness is that, as you go through it, your values are constantly changing. You try to figure out what matters to you, and then you keep figuring it out.

It felt like someone had taken away my credit card and I was having to learn how to budget.

You may decide you want to spend your time working as a neurosurgeon, but two months later, you may feel differently.

Two months after that, you may want to learn to play the saxophone or devote yourself to the church. Death may be a one time event, but living with terminal illness is a process.

I didn’t know. But if I did not know what I wanted, I had learned something, something not found in Hippocrates, Maimonides, or Osler: the physician’s duty is not to stave off death or return patients to their old lives, but to take into our arms a patient and family whose lives have disintegrated and work until they can stand back up and face, and make sense of, their own existence.

There is a tension in the Bible between justice and mercy, between the Old Testament and the New Testament. And the New Testament says you can never be good enough: goodness is the thing, and you can never live up to it. The Main message of Jesus, I believed, is that mercy trumps justice every time.

In the end, it cannot be doubted that each of us can see only a part of the picture.

The doctor sees one, the patient another, the engineer a third, the economist a fourth, the pearl diver a fifth, the alcoholic a sixth, the cable guy a seventh, the sheep farmer an eighth, the Indian beggar a ninth, the pastor a tenth.

Human knowledge is never contained in one person. It grows from the relationships we create between each other and the world, and still it is never complete. And Truth comes somewhere above all of them, where, as at the end of that Sunday’s reading.

“Okay,” she said. “That’s fine. You can stop neurosurgery if, say, you want to focus on something that matters more to you.

But not because you are sick. You aren’t any sicker than you were a week ago. This is a bump in the road, but you can keep your current trajectory. Neurosurgery was important to you.”

When you come to one of the many moments in life where you must give an account of yourself, provide a ledger of what you have been, and done, and meant to the world, do not, I pray, discount that you filled a dying man’s days with a sated joy, a joy unknown to me in all my prior years, a joy that does not hunger for more and more but rests, satisfied. In this time, right now, that is an enormous thing.

EPILOGUE

Sunday evening, Paul’s condition worsened abruptly. He sat on the edge of our bed, struggling to breathe—a startling change. I called an ambulance. When we reentered the emergency room, Paul on a gurney this time, his parents close behind us, he turned toward me and whispered, “This might be how it ends.” “I’m here with you,” I said.

Warm rays of evening light began to slant through the northwest-facing window of the room as Paul’s breaths grew quieter. Cady rubbed her eyes with chubby fists as her bedtime approached, and a family friend arrived to take her home.

I held her cheek to Paul’s, tufts of their matching dark hair similarly askew, his face serene, hers quizzical but calm, his beloved baby never suspecting that this moment was a farewell. Softly I sang Cady’s bedtime song, to her, to both of them, and then released her.

What happened to Paul was tragic, but he was not a tragedy.

On page 115 of this book, he wrote, “You can’t ever reach perfection, but you can believe in an asymptote toward which you are ceaselessly striving.” It was arduous, bruising work, and he never faltered. This was the life he was given, and this is what he made of it. When Breath Becomes Air is complete, just as it is.

Book Review (Personal Opinion):

I cried my soul, heart, and eyes while reading this book. What happened to Paul was tragic, but he wasn’t a tragedy. The way he wrote the passage looked like he was filled with life, but at the same time understanding the menace cancer brought on his life.

When Breath Becomes Air will touch your heart and it will make you reconnect with the sentence often brought up in the book, “Why am I here? What’s the meaning of my life?”

Rating: 10/10

This Book Is For (Recommend):

- A person having someone close struggling with a (deadly) disease

- A young overachiever in the crossroad of their life

- Anyone looking to read a heart-touching story of a life worth living

If You Want To Learn More

Here’s Paul’s wife speaking at Google about Paul and the book.

Google Talks

How I’ve Implemented The Ideas From The Book

When stuff happens to you or to people around you, then you need to make sense out of it. You can find meaning in all the suffering and that will help you find the strength to push forward. This is what I did, pulling the ideas from this book.

One Small Actionable Step You Can Do

There isn’t a small actionable step from this book— there are only big actionable steps. Paul had to listen to his heart multiple times to do the right in his life. And because he did listen, he had a more difficult life. But when his end came (which was at 36), he didn’t feel any regrets because he knew he made the right calls.

So can you— listen to your heart and make the decision even though it’s hard. You never know what tomorrow will bring.