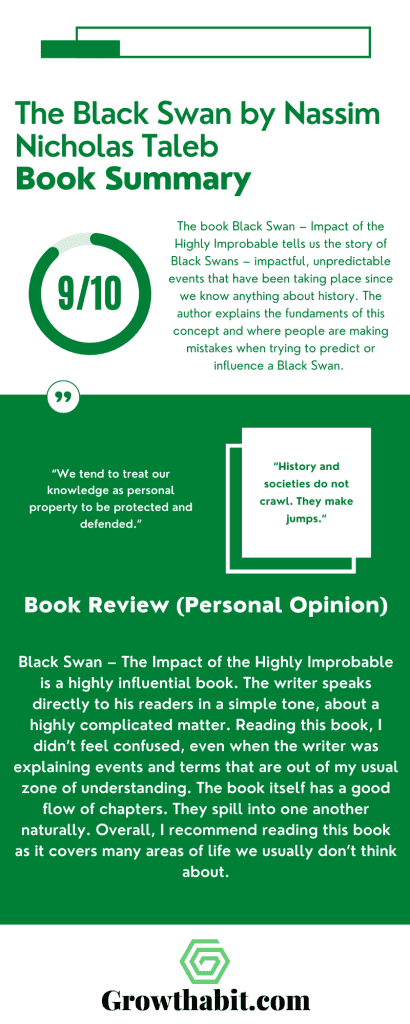

The book Black Swan – Impact of the Highly Improbable tells us the story of Black Swans – impactful, unpredictable events that have been taking place since we know anything about history. The author explains the fundaments of this concept and where people are making mistakes when trying to predict or influence a Black Swan.

Book Title — The Black Swan, Impact of the Highly Improbable

Author— Nassim Nicholas Taleb

Date of Reading— March 2023

Rating— 9/10

What Is Being Said in Detail

Introduction

The introduction starts by explaining the phenomenon of the Black Swan. Black swans were considered to be non-existent in the Old World until one was seen in Australia with its discovery. By discovering a Black swan for the first time, all thoughts and empirical evidence that were done about the color of swans were proven wrong. This event is now a phenomenon for an event that shows, as the author says, the limitation to humankind’s learning for observations or experience and the fragility of our knowledge. This event contains three key attributes: rarity, extreme impact, and retrospective probability. All key events in history are Black swans.

PART ONE – UMBERTO ECO’S ANTILIBRARY, or How We Seek Validation

The first out of four parts is made of 9 chapters, each bringing us closer to the theme of the book – Black Swan phenomenon and its implications. The author will break our viewpoint on what we think we know and help us embrace the idea of the unknown. In the opening of this part, the author suggests we treat our knowledge as personal property to be protected and defended. Therefore, in part one of the book, the author will show us how we deal with knowledge, as a preparation for what is coming next.

CHAPTER ONE – THE APPRENTICESHIP OF AN EMPIRICAL SKEPTIC

The author starts by describing his background as an introduction to the story of a Black Swan. He describes an event that always comes off as a Black Swan – a war. The opening story is told through an example of his youth – the Lebanese civil war. Note that our author is Lebanese. No one was expecting this war, and everyone around him thought it would be different than other wars in the region as if it would end soon.

People understand what is going on in the world better than they understand what is going on around them. Thus, nobody actually knows what is going on when it matters in times of big events, such as Black Swans. Interestingly enough, the author argues how we cannot recognize the pattern and predict these Black Swans impacting us. Not even through analyzing history, since its authors failed to provide us with a lot of different details and small events that are important for generating a Black Swan.

CHAPTER TWO – YEVGENIA’S BLACK SWAN

At the beginning of our second chapter of the book, the author introduces us to Yevgenia Nikolayevna Krasnova – a novelist whose novel was, in fact, a Black Swan. Why? She was trying to get her book published for years, only for authors to say her book would only sell ten copies. It was not until she posted her manuscript online that she got an offer to publish her book. Why is her book a Black Swan? Her book has sold millions of copies without anyone expecting it. The book was translated into 40 different languages! This example is important because it shows how those who fail to see a Black Swan coming (publishers who wouldn’t publish Yevgenia’s book) can indicate all essential factors of the event only after it shows to be a Black Swan.

CHAPTER THREE – THE SPECULATOR AND THE PROSTITUTE

Scalability of a profession. In our labor market, we see two types of occupations – scalable and unscalable. Paid by the hour, task, etc., or paid by the one event in the profession that happened after accumulating numerous amounts of tasks that seemed irrelevant beforehand. The difference between scalable and unscalable jobs is that unscalable ones are Black Swan driven. Waiting for its big moment, no one is expecting.

The problem with scalable jobs is that they can easily be replaced with what has the unscalable profession produced. The author gives an example of music recording. How many people lost their performing jobs around towns only to be replaced with a record? Throughout history, unscalable events have taken place with their size and impact and taken away scalable jobs.

Taleb continues to connect these two types of professions with Extemistan and Mediocristan. Made up concepts that explain the difference between these two types – scalability and impact on the overall outcome.

Extremistan produces Black Swans with huge influences throughout history. Taleb says this is the main idea of this book.

CHAPTER FOUR – ONE THOUSAND AND ONE DAYS OR HOW NOT TO BE A SUCKER

“How to learn from the turkey” is the center of this chapter. Say you are a turkey. Three hundred fifty-four days, your owner feeds you at the same time. On the 365th, you expect the same, no? But you are unfamiliar with the human holiday of Thanksgiving. The turkey problem can be generalized to any situation where the hand that feeds you can be the one that wrings your neck. This chapter bases itself on the Black Swan problem: How can we know the future, given knowledge of the past? When it comes to impactful Black Swans, we are Turkey.

Taleb states that Black Swan is a sucker’s problem. The only way to eliminate it is to keep an open mind. Of course, there are positive Black Swans, but they take time to show their effect, unlike negative ones, which occur quickly.

In this chapter, the author continues to present the Black Swan problem through numerous historical forms. The conclusion is conceived by explaining why we are blind when trying to see Black Swans:

- The error in the confirmation

- Narrative fallacy

- Human nature is not programmed for Black Swans

- What we see is not necessarily there

- We tend to “tunnel.”

CHAPTER FIVE – CONFIRMATION SHMONFIRMATION!

Chapter Five focuses on human nature while acknowledging significant events, especially those not happening. We cannot confirm whether something is happening or not. We can only confirm if they are recognized signs of it. Chapter Five focuses on confirmation bias.

The problem with acknowledging certain events around us is that we, humans, are biased. Therefore, our mind ignores specific details or information around us, mainly the ones that don’t complement what we already know, think, or feel. We subconsciously ignore those signs given to us before an impactful event occurs.

This is something our minds do routinely without realizing it. We have domain-specific thinking and reactions. It implies that our mode of thinking, our intuitions, depends on the context of the matter presented to us. Psychologists call this domain of thinking, and we can have different ones. We do not interpret the same information in a classroom and in real life. This continues with understanding certain problems. We might understand them in school, but not in real life and vice versa.

CHAPTER SIX – THE NARRATIVE FALLACY

Narrative fallacy, or the tendency to over-interpretation and predict stories based on information we have rather than excepting that information for what it is. Through chapter six, the author explains the problem of the narrative fallacy through multiple aspects and examples. We find the narrative fallacy in domains such as finance, business, psychology, and history. We are aware that certain stories are over-simplified, yet we choose to believe in them. The narrative fallacy addresses our limited ability to look at sequences of facts without weaving an explanation into them or, equivalently, forcing a logical link, an _arrow of relationship, __ upon them.

The problem behind having narrative fallacies is that the brain functions often operate outside of our awareness. Problem with perceiving and remembering information correctly author summarizes through three points: information is costly to obtain, information is costly to store, and information is costly to manipulate and retrieve.

Taleb states that there are ways of escaping the concept of narrative fallacy – by making conjectures and running experiments.

When understanding Black Swans, the problem with narrativity lies in messing up our projection of the odds.

Confirmation bias and the narrative fallacy are two internal mechanisms that affect our blindness to Black Swans. In the upcoming chapter, the author will focus on external ones.

CHAPTER SEVEN – LIVING IN THE ANTECHAMBER OF HOPE

As mentioned earlier, people working in unscalable professions tend to hopelessly wait for their moment, believing in the significance of their work. Optimism and hopefulness drive them. However, only a few of them make it. Many people labor under the impression that they are doing something right, yet they may not show solid results for a long time.

Artists, writers, and researchers – all spend time waiting for their big day (that usually never comes). Filled with optimism, these individuals set themselves into dangerous ways of making their life choices. They continuously hope to fulfill their purpose by optimistically believing and working on them. Rather than approaching hope with optimism, our author suggests we should take a more realistic approach, not run by emotions.

CHAPTER EIGHT – GIACOMO CASANOVA’S UNFAILING LUCK: THE PROBLEM OF SECRET EVIDENCE

In chapter eight, the author provides us with another dimension of experiments and empirical findings. Among many examples, he states the following one: Take an empirical study of gamblers. It shows that many of the big gamblers had a lot of luck at the beginning. However, the study doesn’t consider that those who did not have been lucky at their start gave up on gambling immediately after their first failure. The study has been done with “current” gamblers, ignoring the fact that they are, in fact, gambling simply because they stuck around because of their luck—those who didn’t make it into this study.

The author introduces us to the concept of ludic fallacy – relying on empirical and math findings only for them not to be reliable. This is especially important for Black Swans, as empirics try to predict unpredictability while not including numerous important pieces of information in their calculations. Taleb suggests embracing randomness rather than trying to run from it.

CHAPTER NINE – THE LUDIC FALLACY OR THE UNCERTAINTY OF THE NERD

Chapter Nine starts with the author giving examples of two different types of observers through the same problem. The first one is Brooklyn Tony, an Italian who is what they call street smart. Tony earns a fine amount for living through making different types of arrangements with daily business partners.

On the other hand, we have the nerd – Dr. John. The problem is the following: What are the chances of a coin flipping on tails if the previous 99 times it flipped on heads? Dr. John says the chances are 50:50. Regular statistical approach. On the other hand, Brooklyn Tony suggests it will flip on heads since there must be a catch – one side is made heavier than the other, for example.

Taleb guides us to recognize the concept of thinking inside the box – a very general problem – Ludic fallacy, as our author calls it. These types of inside-the-box thinking often come with a bell curve – whose big tendency of usage by empiricists and mathematicians, we will see, irritate our author significantly.

PART TWO – WE JUST CAN’T PREDICT

Message to the reader: We can not predict. The epicenter of the Black Swan problem – we try to predict the unpredictable, ignoring its unpredictability. Through chapters ten to thirteen, our author will focus on explaining how much we think inside the box. The larger the role of the Black Swan, the harder it will be for us to predict.

CHAPTER TEN – THE SCANDAL OF PREDICTION

Chapter ten is the opening chapter of the second part of our book. Two key topics of this chapter are: We are demonstrably arrogant about what we think we know and the Implications of this arrogance of ours for all activities, including prediction.

The author argues that we are not wise enough to be trusted with knowledge. He continues to demonstrate this idea through the following example: whenever scientists do research on people’s prediction of amounts they don’t previously know – the expected error is percent, and the actual one turns out to be 45 percent. We overestimate what we know and underestimate uncertainty.

This is what happens with Black Swans – people who try to predict them either underestimate them or severely overestimate them. Taleb continues by explaining to us the key difference between predicting (what has not taken place yet) and guessing (what I don’t know, but someone else may know).

Predictions became less based on technological development, as we rely too much on created computer models rather than our own sense of clear judgment. The additional problem is that we tend to be biased and grasp small details which we predicted right while predicting the main Black Swan completely wrongly.

The key takeaway is the following: The tendency to predict is a fallacy. Spending time on predictions of the Black Swan is a waste of time, as we should build systems that merely prepare us for unexpected events.

CHAPTER ELEVEN – HOW TO LOOK FOR BIRD POOP

Chapter eleven goes deeper into our limitations to predict. Many discoveries, as we know, came from human arrogance. As our author states: The classical model of discovery is as follows: you search for what you know (say, a new way to reach India) and find something you didn’t know was there (America).

What is more, those that look for evidence in search of the next Black Swan tend to overlook it or not see it, while those who do not look often find it. We take lasers for example. Their inventor was made fun of because it had no purpose when it was discovered – he discovered something useless. Later on, lasers are used for compact discs, eyesight corrections, microsurgery, data storage, etc.

Prediction requires knowing about technologies that will be discovered in the future. But that very knowledge would almost automatically allow us to start developing those technologies right away. Ergo, we do not know what we will know.

The moral of chapter eleven: trying to predict specific events is the main fault of our projections. On the contrary, we should be humbler about what we think we know and what we are certain of. Recognizing the limits of our predictions is crucial.

CHAPTER TWELVE – EPISTEMOCRACY, A DREAM

Chapter twelve introduces us to the term Epistemocracy. Epistemic humility is a trait of people who tend to introspect and question their own knowledge of things – epistemocrats. The author highlights how only epistemocrats would make Utopia possible, as epistemocratic leaders are the ones we need but never the ones we get. Taleb continues chapter twelve by giving us yet another problem of human nature – “future blindness .”

It seems we can not comprehend that tomorrow wasn’t just another yesterday we’ve already experienced. Furthermore, scientists have found evidence of mental blocks and distortions in the way we fail to learn from our past errors in the projection of the future. This is what makes people unable to predict Black Swans, even when they want to. People tend not to believe in randomness, even though Black Swans are generated by it.

CHAPTER THIRTEEN – APELLES THE PAINTER, OR WHAT YOU DO IF YOU CANNOT PREDICT

Through chapter thirteen, the final chapter of the second part of our book, the author guides us with what we should do now that we understand the concept of a Black Swan. There are two key lessons to understand here.

The first lesson is to be human. It is okay to be epistemically arrogant. It is what we are. The trick is to be a fool in the places. For instance, being certain you will take your family to a picnic tomorrow is okay. You are forecasting a small thing with no great impact on your life. Avoid predicting government social security forecasts for the year 2040. You can predict, but don’t be narrow-minded about your predictions.

The second lesson is that we can take advantage of the problem of prediction. The author provides us with a few tricks regarding this lesson. The first one is to distinguish between positive and negative contingencies. The second one is to not be narrow-minded by looking only for precise and local Black Swans. The third one is to seize any opportunity, as they are much rarer than we think. This especially implies positive Black Swans. Forth one is to beware of precise plans by governments, as not all of them are good. The fifth and final one is not to try to convince people who do not want to understand your point.

PART THREE – Those Gray Swans of Extremistan

The third part of our book covers chapters fourteen to eighteen. After the author has given us the idea of what a Black Swan is and our inability to predict one, it’s time to focus on the mentioned aspects of why that is. Through these four chapters, the author helps us to deeper understand Mediocristan and Extremistan, randomness, Gaussian bell curve, and unpredictability of every impactful thing we are trying to predict.

CHAPTER FOURTEEN – FROM MEDIOCRISTAN TO EXTREMISTAN, AND BACK

Chapter fourteen starts with the author giving frightening examples of randomness and how it affects our society. We can see this through income inequalities between professions or even inside professions. Few individuals take the biggest part of the pie, leaving the others to share a small piece. One of the reasons for this is that failure is cumulative – losers are likely to also lose in the future.

Preferential attachment is another concept author brings us closer with further on chapter fourteen. For instance – the more people aggregate in a particular city, the more likely a stranger will pick that city as their destination. The big get bigger, and the small stay small. The same model can be used for contagions and concentration of ideas. They spread because they have carriers. This is a great example of what we previously called Extremistan. This problem is solvable by concepts society is drifting away from – communism, religion, etc. This is why Extremistan is here to stay.

CHAPTER FIFTEEN – THE BELL CURVE, THE GREAT INTELLECTUAL FRAUD

Chapter Fifteen is solely focused on the bell curve. The Bell curve is used as a risk-measurement tool. The main point is that most observations hover around the mediocre, the average: the odds of deviation decline faster and faster as you move away from the average. The Gaussian-bell curve variations face a headwind that makes probabilities drop at a faster and faster rate as you move away from the mean, while “scalable”, or Mandelbrotian variations, do not have such a restriction. Overall, our author criticizes the over-usage of the bell curve, as he believes alternatives should be found.

CHAPTER SIXTEEN – THE AESTHETICS OF RANDOMNESS

Chapter seventeen focuses on fractals. Fractal is a word meant to describe the geometry of the rough and broken. The author explains to us the nature of fractals, as they can help us to understand the randomness of the world we live in.

The moral is: things in nature are quite repetitive, and we can always increase our understanding of things around us if we continue looking for details inside details – fractals. The key here is that _the fractal has numerical or statistical measures that are (somewhat) preserved across scales__–the ratio is the same, unlike the Gaussian.

The idea of fractals links all parts of the book. The author suggests we should, amongst our usual sciences, study randomness around us. This would give us better insight into the problems and flow of events in the real world. “Attempt to be predictive” and “Avoid forecasters” are messages the author sends us at the end of this chapter.

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN – LOKE’S MADMEN, OR BELL CURVE IN THE WRONG PLACES

As our author says: This chapter examines disasters stemming from the application of phony mathematics to social science. People’s minds are domain-dependent. Gaussian tools, such as the bell curve, give them numbers, which seem to be “better than nothing.”

They anchor onto a number when making a statement or, even worse – a prediction. Society seems to reward this type of behavior, especially through Nobel prizes. The problem with these types of mathematized formulas is that they do not have realistic assumptions and do not produce reliable results.

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN – THE UNCERTAINTY OF THE PHONY

This final chapter of Parth Tree focuses on a major ramification of the ludic fallacy: how those whose job it is to make us aware of uncertainty fail us and divert us into bogus certainties through the back door.

All theories built around the ludic fallacy ignore a layer of uncertainty. We can not be certain of political events, weather, or social events – we can not predict them accurately. So whenever you hear about experts in this field – it is most likely that they are phony. The point of the chapter is to be aware of the things that we can not be aware of. Keeping an open mind and accepting randomness is the key to a better understanding of our environment.

PART FOUR – THE END

CHAPTER NINETEEN – HALF AND HALF, OR HOW TO GET WITH THE BLACK SWAN

Chapter nineteen contains final suggestions and advice from the author regarding the Black Swan. For instance, consider this: Missing a train is only painful if you run after it. Don’t chase what you can not make. You can always control your side of actions in order not to be disappointed. You make your own end. The author reminds us that us being alive is an extraordinary piece of good luck, a chance occurrence of monstrous proportions. Therefore we should make the best out of it.

Most Important Keywords, Sentences, Quotes

PART ONE

“We tend to treat our knowledge as personal property to be protected and defended.”

CHAPTER ONE

“History is opaque. You see what comes out, not the script that produces events, the generator of history.”

“The studious examination of the past in the greatest of detail does not teach you much about the mind of History; it only gives you the illusion of understanding it.”

“History and societies do not crawl. They make jumps.”

“Categorizing always produces reduction in true complexity. It is a manifestation of the Black Swan generator.”

CHAPTER TWO

“Publishers now have a theory that “truck drivers who read books do not read books written for truck drivers” and hold that “readers despise writers who pander to them.”

CHAPTER THREE

“A second-year Wharton student told me to get a profession that is “scalable,” that is, one in which you are not paid by the hour and thus subject to the limitations of the amount of your labor.”

“Your revenue depends on your continuous efforts more than on the quality of your decisions.”

“What we call “talent” generally comes from success, rather than its opposite.”

“They are near-Black Swans. They are somewhat tractable scientifically–knowing about their incidence should lower your surprise; these events are rare but expected. I call this special case of “gray” swans Mandelbrotian randomness.”

CHAPTER FOUR

“Something has worked in the past, until–well, it unexpectedly no longer does, and what we have learned from the past turns out to be at best irrelevant or false, at worst viciously misleading.”

“The tragedy of capitalism is that since the quality of the returns is not observable from past data, owners of companies, namely shareholders, can be taken for a ride by the managers who show returns and cosmetic profitability but in fact might be taking hidden risks.”

Narrative fallacy – the tendency of people to create simple and flawed stories out of a sequence of facts to make sense of the world

CHAPTER FIVE

“Unless we concentrate very hard, we are likely to unwittingly simplify the problem because our minds routinely do so without our knowing it.”

“Our reactions, our mode of thinking, our intuitions, depend on the context in which the matter is presented, what evolutionary psychologists call the “domain” of the object or the event.”

“All pieces of information are not equal in importance.”

Confirmation bias – the tendency of people to favor information that confirms or strengthens their beliefs or values and is difficult to dislodge once affirmed.

CHAPTER SIX

“We like stories, we like to summarize, and we like to simplify, i.e., to reduce the dimension of matters. The first of the problems of human nature that we examine in this section, the one just illustrated above, is what I call the _narrative fallacy.”

“Our propensity to impose meaning and concepts blocks our awareness of the details making up the concept.”

“Narrativity can viciously affect the remembrance of past events as follows: we will tend to more easily remember those facts from our past that fit a narrative, while we tend to neglect others that do not _appear__ to play a causal role in that narrative.”

“There are two varieties of rare events: a) the _narrated__ Black Swans, those that are present in the current discourse and that you are likely to hear about on television, and b) those nobody talks about, since they escape models–those that you would feel ashamed discussing in public because they do not seem plausible.”

CHAPTER SEVEN

“We favor the sensational and the extremely visible. This affects the way we judge heroes. There is little room in our consciousness for heroes who do not deliver visible results–or those heroes who focus on process rather than results.”

“Your happiness depends far more on the number of instances of positive feelings, what psychologists call “positive affect,” than on their intensity when they hit. In other words, good news is good news first; _how__ good matters rather little.”

CHAPTER EIGHT

“There is a vicious attribute to the bias: it can hide best when its impact is largest.”

“There is a belief among gamblers that beginners are almost always lucky. “It gets worse later, but gamblers are always lucky when they start out,” you hear. This statement is actually empirically true: researchers confirm that gamblers have lucky beginnings. Those who start gambling will be either lucky or unlucky (given that the casino has the advantage, a slightly greater number will be unlucky). The lucky ones, with the feeling of having been selected by destiny, will continue gambling; the others, discouraged, will stop and will not show up in the sample.”

“It is much easier to sell “Look what I did for you” than “Look what I avoided for you”.”

CHAPTER NINE

“A nerd is simply someone who thinks exceedingly inside the box.”

“One of its nastiest illusions is what I call the ludic fallacy–the attributes of the uncertainty we face in real life have little connection to the sterilized ones we encounter in exams and games.”

“Just as we tend to underestimate the role of luck in life in general, we tend to overestimate it in games of chance.”

PART TWO

“We tend to “tunnel” while looking into the future, making it business as usual, Black Swan-free, when in fact there is nothing usual about the future.”

“The larger the role of the Black Swan, the harder it will be for us to predict.”

CHAPTER TEN

“We are simply not wise enough to be trusted with knowledge.”

“Epistemic arrogance bears a double effect: we overestimate what we know, and underestimate uncertainty, by compressing the range of possible uncertain states (i.e., by reducing the space of the unknown).

Epistemic humility – critically reflecting on our ontological commitments, one’s beliefs and belief system, one’s biases, and one’s assumptions, and being willing to change or modify them.

“The more information you give someone, the more hypotheses they will formulate along the way, and the worse off they will be. They see more random noise and mistake it for information.”

“The problem is that our ideas are sticky: once we produce a theory, we are not likely to change our minds–so those who delay developing their theories are better off.”

“You cannot ignore self-delusion. The problem with experts is that they do not know what they do not know. Lack of knowledge and delusion about the quality of your knowledge come together–the same process that makes you know less also makes you satisfied with your knowledge.

CHAPTER ELEVEN

If you think that the inventions we see around us came from someone sitting in a cubicle and concocting them according to a timetable, think again: almost everything of the moment is the product of serendipity.

Serendipity: the occurrence and development of events by chance in a happy or beneficial way.

“As happens so often in discovery, those looking for evidence did not find it; those not looking for it found it and were hailed as discoverers.”

CHAPTER TWELVE

“There is a blind spot: when we think of tomorrow, we do not frame it in terms of what we thought about yesterday or the day before yesterday.”

“We grossly overestimate the length of the effect of misfortune on our lives. You think that the loss of your fortune or current position will be devastating, but you’re probably wrong.”

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

“The lesson for the small is: _be human! Accept that being human involves some amount of epistemic arrogance in running your affairs. Do not be ashamed of that. Do not try to always withhold judgment—opinions are the stuff of life. Do not try to avoid predicting–yes, after this diatribe about prediction I am _not__ urging you to stop being a fool. Just be a fool in the right places.”

“Knowing that you cannot predict does not mean that you cannot benefit from unpredictability.”

PART THREE

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

“Failure is also cumulative; losers are likely to also lose in the future, even if we don’t take into account the mechanism of demoralization that might exacerbate it and cause additional failure.”

“Ideas do not spread without some kind of structure”

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

“The main point of the Gaussian, as I’ve said, is that most observations hover around the mediocre, the average; the odds of a deviation decline faster and faster (exponentially) as you move away from the average.”

“If you must have only one single piece of information, this is the one: the dramatic increase in the speed of decline in the odds as you move away from the center, or the average.”

“Remember this: the Gaussian-bell curve variations face a headwind that makes probabilities drop at a faster and faster rate as you move away from the mean, while “scalables,” or Mandelbrotian variations, do not have such a restriction. That’s pretty much most of what you need to know.”

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

“Fractality__ is the repetition of geometric patterns at different scales, revealing smaller and smaller versions of themselves. Small parts resemble to some degree, the whole.”

“I said earlier that some Black Swans arise because we ignore sources of randomness. Others arise when we overestimate the fractal exponent. A gray swan concerns modelable extreme events, a black swan is about unknown unknowns.”

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

“People want a number to anchor on. Yet the two methods are logically incompatible.”

“The problem of course is that these Gaussianizations do not have realistic assumptions and do not produce reliable results. They are neither realistic nor predictive”

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

“Can Philosophers Be Dangerous to Society? People who worry about pennies instead of dollars can be dangerous to society. They are wasting our studies of uncertainty by focusing on the insignificant.”

“Our tendency is to be very rational, except when it comes to the Black Swan.”

“Missing a train is only painful if you run after it!”

“It is more difficult to be a loser in a game you set up yourself.”

PART FOUR

CHAPTER NINETEEN

“Having plenty of data will not provide confirmation, but a single instance can disconfirm.”

Book Review (Personal Opinion):

Black Swan – The Impact of the Highly Improbable is a highly influential book. The writer speaks directly to his readers in a simple tone, about a highly complicated matter. Reading this book, I didn’t feel confused, even when the writer was explaining events and terms that are out of my usual zone of understanding. The book itself has a good flow of chapters. They spill into one another naturally. Overall, I recommend reading this book as it covers many areas of life we usually don’t think about.

Rating: 9/10

This Book Is For:

- University students that are about to start their career

- Anyone who wishes to shift their way of understanding everyday life

- People who want to expand their views and deeper their understanding of everyday things happening around us

If You Want to Learn More

Nassim Nicholas Taleb talks more about his book and what the Black Swan is through the following speech:

How I’ve Implemented the Ideas From The Book

The Black Swan gave me another dimension of everyday happenings in the world, in a way that I haven’t experienced before. It motivated me to be more open-minded and embrace what is coming, even if it’s unexpected.

One Small Actionable Step You Can Do

Do not try to narrowly predict any influential event. Keep an open mind when thinking about what the future holds. Understand what you can impact, and what you cannot. This will make your life easier.