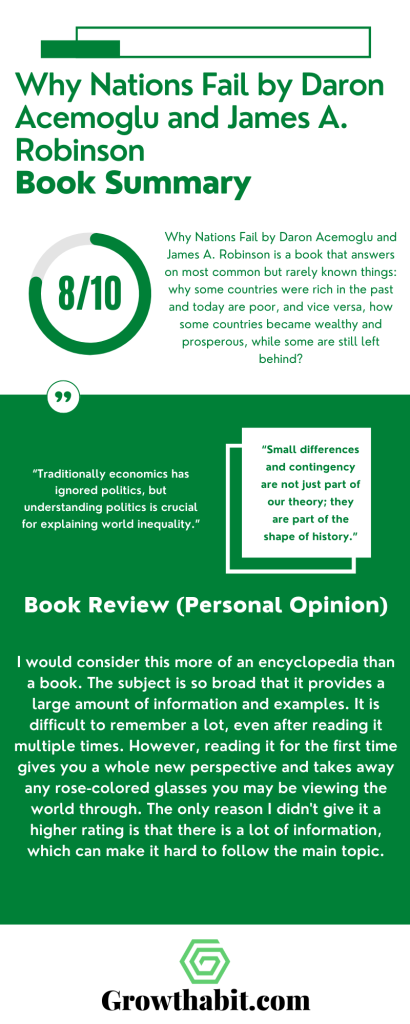

Why Nations Fail by Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson is a book that answers on most common but rarely known things: why some countries were rich in the past and today are poor, and vice versa, how some countries became wealthy and prosperous, while some are still left behind?

Book Title: Why Nations Fail (The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty)

Authors: Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson

Date of Reading: March 2023

Rating: 8/10

What Is Being Said In Detail:

The book narrates about theories and ways institutions were created in the past. It provides a story for every case and makes a comparison in order of time and place.

The book includes numerous detailed examples of popular revolutions, theories, wars, and other significant events. It is structured into fifteen chapters and features photos and maps as descriptions.

Preface

The preface gives a superficial scratch of the diversity between the United States and Egypt’s standard of living. You can see a short history brief and get answers about the theme of this book – why is Egypt so much poorer than the USA, and what is their brake for development?

Chapter One: “So Close and Yet So Different”

Chapter 1, at the very beginning, gives you an in-depth explanation of two places – Nogales, Arizona, and Nogales, Sonora, so similar, but with a huge difference.

Although this chapter is just a rough presentation of the rest of the book, it will explain why geographical, cultural, and even educational differences are not the reason for success or failure. These two cities are examples of the same geography and culture, but very different incomes. Why?

The authors claim that the most essential reason is political institutions if they are inclusive or extractive. The beauty of this book lies in the rest of this chapter – profound historical examples and research on how these political systems were made.

Chapter Two: “Theories That Don’t Work”

Chapter 2, relying on the first one, will explain three accepted but irrelevant theories about the failure of nations. The first one is a geography factor like The Diamond Theory.

But there is an example of North and South Korea that refutes this factor. The second one will be cultural theory, like the differences between the work ethics within nations; but we have USA and Mexico, two countries with the same culture, but huge life standard differences. And the last one is about the ignorance of the leaders.

And as you can guess, this theory also doesn’t work because there were a lot of leaders in one nation, and they had expert pieces of advice but didn’t achieve any economic growth.

Chapter Three: “The Making of Prosperity and Poverty”

Chapter 3 discusses the concept of inclusive and extractive institutions, which was mentioned at the beginning. There are numerous examples of both types of institutions, but the difference between South and North Korea is the clearest.

The main distinction is the economic and political factors: in inclusive institutions, citizens have the right to participate in these areas through opportunities provided by their country, while in extractive institutions, there is a lack of such opportunities, so it leads to unstable education, infrastructure, and other areas of society.

Chapter Four: “Small Differences and Critical Junctures: The Weight of History”

Chapter 4 begins with the example of the Black Death pandemic as a critical juncture in the 14th century.

Since the future is not predictable, there are always wars, pandemics, or revolutions, points that can impact one society and bring it an opportunity to change its economic and political system and grow.

The Black Death is such an example for European countries. Besides this, slight differences like initial conditions can play a big role in the turning point.

Here we have an example of England and France where England had a relatively decentralized feudal system, and it was easier to change it into an inclusive one. In contrast, France’s system was highly centralized and more difficult to change.

Chapter Five: “I’ve Seen the Future, and It Works: Growth Under Extractive Institutions”

Chapter 5 talks about colonialism and its hard impact on the creation of extractive institutions. The interesting part of colonialism is the fast growth that happens at the beginning.

So in this chapter, the authors provided a story about Maya citizens and the Soviet Union, with light periods and technological development.

But as central political leaders highly limit their citizens, there isn’t enough power and creative destruction to make that growth sustainable.

Chapter Six: “Drifting Apart”

Chapter 6 talks about evolving institutions and their differences according to the different places. One of the examples is Venice and its great institutions and economy that was brilliant during the Middle Ages.

They also had a powerful political system that allowed rules of law to their citizens and made Venice one of the heaviest cities in Europe.

But, another crucial key of inclusive institutions is synchronous updates of ideas and development to improve your growth. So, that was the problem here, and that is the reason why Venecia today has income mostly from tourists.

Chapter Seven: “The Turning Point”

Chapter 7 mentions the historical development of England. As with every country, England also had political conflicts, which led to different results, so the authors here discuss Civil War, Magna Carta, and the Glorious Revolution.

All of these conflicts made a strong inclusive political and economic system, and they were forerunners for the Industrial Revolution.

So, all those points made England the most affected country by the Industrial Revolution and made a space for technological development – they were ready for new ideas making susceptible terrain for growth by allowing their citizens much more laws and freedom than other countries at that period.

Chapter Eight: “Not on Our Turf: Barriers to Development”

Chapter 8 gives the opposite example from the previous one. While England developed through revolutions, the rest of Europe, such as the Austria-Hungary Empire, were afraid of the creative destruction revolutions and inclusive institutions bring with them.

Because of that fear, they prohibited some innovations in their country which undegraded their development. Then, countries like Ethiopia and Somalia were stopped by the absolutist regime that led them to be one of the poorest countries in the world.

Chapter Nine: “Reversing Development”

Chapter 9 provides another important reason for nations’ failure – world inequality. This part of the book talks about slaves – the Africans in the first place, and the negative impact of colonialism on economic growth and prosperity.

In that regard, there is an example of a “dual economy”, again in African countries, another example of inequality under the extractive system.

This economy means that in one area are modern and traditional lifestyles and practically every segment of life is divided. That ended in the past Century with protests.

Chapter Ten: “The Diffusion of Prosperity”

Chapter 10 continues the story about inclusive institutions and the way they were created in the past.

In the previous chapter we can read about England’s history but there are other methods of creating an inclusive system that also worked, such as systems in the United States, Australia, and French.

There we have a deep discussion of the French aristocracy and the French Revolution that helped this country to make a better environment for economic and technological growth by creating a more open society and including their participants in political life.

Chapter Eleven: “The Virtuous Circle”

Chapter 11 presents an important topic when it comes to a sustainable inclusive system. It highlights the role of inclusive economic institutions in creating a virtuous circle.

From a bunch of examples of how some action or law can represent the beginning of this circle, we can mark the Industrial Revolution in the UK. Events like that made changes and encouraged society to work in favor of the common good and growth.

Chapter Twelve: “The Vicious Circle”

Chapter 12, in contrast to the previous one, talks about the vicious circle that the extractive system creates and that is deserved for underdevelopment and poverty.

They also create social inequality, and what is much worse, they are hard to break. The provided example is the African country, Sierra Leone, and its extractive system that creates a circle of lack of healthcare, education, and infrastructure.

Chapter Thirteen: “Why Nations Fail Today”

Chapter 13 once more repeats the main reasons for nations’ failure. As we already know, extractive institutions it is. But this chapter discusses another important thing – state failure.

As a result of an extractive system, looking deeper into the country’s organization, we can see a lack of functionality in the state part. It is mostly unsecured and focused on the elites of the political system, not the whole society, which leads the country to failure.

Chapter Fourteen: “Breaking The Mold”

Chapter 14 gives examples through the history of countries that broke the barrier and started to convert their extractive system into an inclusive one.

The chapter covers the story of Black protests in the USA and the breaking of Communists in China after Mao Tse Tung’s death.

The importance of small steps is crucial at this point, as well as knowing what the right step is at the right moment because every nation is specific – there is no universal schema for this conversion.

Chapter Fifteen: “Understanding Prosperity and Poverty”

Chapter 15 concludes the main things being said in the previous chapters.

It highlights some events speaking about the past, present, and future, making sure that everything from this book is something that happened because of some crucial junctures through history, and it could be highly different.

Speaking about the future, we are supposed to see that some countries, like China, today have solid growth in an economic way, but with knowledge from this book we can see that is not a highly inclusive system, and in order of that, it would be prosperity for long years.

Most Important Keywords, Sentences, Quotes:

PREFACE

“THIS BOOK IS about the huge differences in incomes and standards of living that separate the rich countries of the world, such as the United States, Great Britain, and Germany, from the poor, such as those in sub-Saharan Africa, Central America, and South Asia.”

“The roots of discontent in these countries lie in their poverty. The average Egyptian has an income level of around 12 percent of the average citizen of the United States and can expect to live ten fewer years; 20 percent of the population is in dire poverty.

Though these differences are significant, they are actually quite small compared with those between the United States and the poorest countries in the world, such as North Korea, Sierra Leone, and Zimbabwe, where well over half the population lives in poverty.

CHAPTER ONE: “So Close and Yet So Different”

“At this point the Spanish focused on the people of the Inca Empire. As in Mexico, citizens were divided into encomiendas, with one going to each of the conquistadors who had accompanied Pizarro.

The encomienda was the main institution used for the control and organization of labor in the early colonial period, but it soon faced a vigorous contende.”

“In Acomayo they ask intrepid foreigners, “Don’t you know that the people here are poorer than the people over there in Calca? Why would you ever want to come here?”

Intrepid because it is much harder to get to Acomayo from the regional capital of Cusco, ancient center of the Inca Empire, than it is to get to Calca. The road to Calca is surfaced, the one to Acomayo is in a terrible state of disrepair.”

“Though these institutions generated a lot of wealth for the Spanish Crown and made the conquistadors and their descendants very rich, they also turned Latin America into the most unequal continent in the world and sapped much of its economic potential.”

“It was Smith who was the first to realize that the model of colonization that had worked so well for Cortés and Pizarro simply would not work in North America.

The underlying circumstances were just too different. Smith noted that, unlike the Aztecs and Incas, the people of Virginia did not have gold. Indeed, he noted in his diary, “Victuals you must know is all their wealth.””

“We live in an unequal world. The differences among nations are similar to those between the two parts of Nogales, just on a larger scale.”

“The reason that Nogales, Arizona, is much richer than Nogales, Sonora, is simple; it is because of the very different institutions on the two sides of the border, which create very different incentives for the inhabitants of Nogales, Arizona, versus Nogales, Sonora.

The United States is also far richer today than either Mexico or Peru because of the way its institutions, both economic and political, shape the incentives of businesses, individuals, and politicians.

Each society functions with a set of economic and political rules created and enforced by the state and the citizens collectively.”

CHAPTER TWO: “Theories That Don’t Work”

“One widely accepted theory of the causes of world inequality is the geography hypothesis, which claims that the great divide between rich and poor countries is created by geographical differences.”

“History illustrates that there is no simple or enduring connection between climate or geography and economic success. For instance, it is not true that the tropics have always been poorer than temperate latitudes.”

“Finally, geographic factors are unhelpful for explaining not only the differences we see across various parts of the world today but also why many nations such as Japan or China stagnate for long periods and then start a rapid growth process. We need another, better theory.”

“Is the culture hypothesis useful for understanding world inequality? Yes and no.

Yes, in the sense that social norms, which are related to culture, matter and can be hard to change, and they also sometimes support institutional differences, this book’s explanation for world inequality.

But mostly no, because those aspects of culture often emphasized—religion, national ethics, African or Latin values—are just not important for understanding how we got here and why the inequalities in the world persist.”

“The final popular theory for why some nations are poor and some are rich is the ignorance hypothesis, which asserts that world inequality exists because we or our rulers do not know how to make poor countries rich.”

“Traditionally economics has ignored politics, but understanding politics is crucial for explaining world inequality.”

CHAPTER THREE: “The Making of Prosperity and Poverty”

“[…] the average North Korean can expect to live ten years less than his cousins south of the 38th parallel. Map 7 illustrates in a dramatic way the economic gap between the Koreas.

It plots data on the intensity of light at night from satellite images. North Korea is almost completely dark due to lack of electricity; South Korea is blazing with light.”

“Inclusive economic institutions, such as those in South Korea or in the United States, are those that allow and encourage participation by the great mass of people in economic activities that make the best use of their talents and skills and that enable individuals to make the choices they wish.”

“We call such institutions, which have opposite properties to those we call inclusive, extractive economic institutions—extractive because such institutions are designed to extract incomes and wealth from one subset of society to benefit a different subset.”

“ The price these nations pay for low education of their population and lack of inclusive markets is high. They fail to mobilize their nascent talent.

They have many potential Bill Gateses and perhaps one or two Albert Einsteins who are now working as poor, uneducated farmers, being coerced to do what they don’t want to do or being drafted into the army because they never had the opportunity to realize their vocation in life.”

CHAPTER FOUR: “Small Differences and Critical Junctures: The Weight of History”

“The Black Death is a vivid example of a critical juncture, a major event or confluence of factors disrupting the existing economic or political balance in society. A critical juncture is a double-edged sword that can cause a sharp turn in the trajectory of a nation.”

“World inequality dramatically increased with the British, or English, Industrial Revolution because only some parts of the world adopted the innovations and new technologies that men such as Arkwright and Watt, and the many who followed, developed.”

CHAPTER FIVE: “I’ve Seen the Future, and It Works: Growth Under Extractive Institutions”

“Soviet Russia,” he recalled in his 1931 autobiography, “was a revolutionary government with an evolutionary plan.

Their plan was not to end evils such as poverty and riches, graft, privilege, tyranny, and war by direct action, but to seek out and remove their causes.

They had set up a dictatorship, supported by a small, trained minority, to make and maintain for a few generations a scientific rearrangement of economic forces which would result in economic democracy first and political democracy last.”

“Right up until the early 1980s, many Westerners were still seeing the future in the Soviet Union, and they kept on believing that it was working. In a sense it was, or at least it did for a time.”

“Allowing people to make their own decisions via markets is the best way for a society to efficiently use its resources.

When the state or a narrow elite controls all these resources instead, neither the right incentives will be created nor will there be an efficient allocation of the skills and talents of people.”

“Extractive institutions are so common in history because they have a powerful logic: they can generate some limited prosperity while at the same time distributing it into the hands of a small elite.”

CHAPTER SIX: “Drifting Apart”

“Today the only economy Venice has, apart from a bit of fishing, is tourism. Instead of pioneering trade routes and economic institutions, Venetians make pizza and ice cream and blow colored glass for hordes of foreigners. […] Venice went from economic powerhouse to museum.”

“Another fascinating way to ¸find evidence of economic growth is from the Greenland Ice Core Project. As snowflakes fall, they pick up small quantities of pollution in the atmosphere, particularly the metals lead, silver, and copper.

The snow freezes and piles up on top of the snow that fell in previous years. his process has been going on for millennia and provides an unrivaled opportunity for scientists to understand the extent of atmospheric pollution thousands of years ago.”

“The experience of economic growth during the Roman Republic was impressive, as were other examples of growth under extractive institutions, such as the Soviet Union.

But that growth was limited and was not sustained, even when it is taken into account that it occurred under partially inclusive institutions.

Growth was based on relatively high agricultural productivity, significant tribute from the provinces, and long-distance trade, but it was not underpinned by technological progress or creative destruction.”

CHAPTER SEVEN: “The Turning Point”

“The stocking frame was an innovation that promised huge productivity increases, but it also promised creative destruction.”

“Technological innovation makes human societies prosperous, but also involves the replacement of the old with the new, and the destruction of the economic privileges and political power of certain people.

For sustained economic growth we need new technologies, new ways of doing things, and more often than not they will come from newcomers such as Lee.”

“It was the inclusive nature of English institutions that allowed this process to take place. Those who suffered from and feared creative destruction were no longer able to stop it.”

CHAPTER EIGHT: “Not on Our Turf: Barriers to Development”

“In addition to serfdom, which completely blocked the emergence of a labor market and removed the economic incentives or initiative from the mass of the rural population, Habsburg absolutism thrived on monopolies and other restrictions on trade.

The urban economy was dominated by guilds, which restricted entry into professions. Until 1775 there were internal tariffs within Austria itself and in Hungary until 1784.

There were very high tariffs on imported goods, with many explicit prohibitions on the import and export of goods.”

“Opposition to innovation was manifested in two ways. First, Francis I was opposed to the development of industry. Industry led to factories, and factories would concentrate poor workers in cities, particularly in the capital city of Vienna.

Those workers might then become supporters for opponents of absolutism. […] Second, he opposed the construction of railways, one of the key new technologies that came with the Industrial Revolution.

When a plan to build a northern railway was put before Francis I, he replied, No, no, I will have nothing to do with it, lest the revolution might come into the country.”

“As the process of industrialization was underway in other parts of the world in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Somalis were feuding and fending for their lives, and their economic backwardness became more ingrained.”

CHAPTER NINE: “Reversing Development”

“The “dual economy” paradigm, originally proposed in 1955 by Sir Arthur Lewis, still shapes the way that most social scientists think about the economic problems of less-developed countries.

According to Lewis, many less-developed or underdeveloped economies have a dual structure and are divided into a modern sector and a traditional sector.

The modern sector, which corresponds to the more developed part of the economy, is associated with urban life, modern industry, and the use of advanced technologies.

The traditional sector is associated with rural life, agriculture, and “backward” institutions and technologies.”

“Tribal tenure is a guarantee that the land will never properly be worked and will never really belong to the natives. Cheap labour must have a cheap breeding place, and so it is furnished to the Africans at their own expense.”

“The dual economy of South Africa did come to an end in 1994. But not because of the reasons that Sir Arthur Lewis theorized about. It was not the natural course of economic development that ended the color bar and the Homelands.

Black South Africans protested and rose up against the regime that did not recognize their basic rights and did not share the gains of economic growth with them.”

CHAPTER TEN: “The Diffusion of Prosperity”

“As we have seen, by this time the most extreme form of serfdom, which tied people to the land and forced them to work for and pay dues to the feudal lords, was long in decline in France.

Nevertheless, there were restrictions on mobility and a plethora of feudal dues that the French peasants were required to pay to the monarch, the nobility, and the Church.”

“But perhaps what was most radical, even unthinkable at the time, was the eleventh article, which stated: All citizens, without distinction of birth, are eligible to any office or dignity, whether ecclesiastical, civil, or military; and no profession shall imply any derogation.”

CHAPTER ELEVEN: “The Virtuous Circle”

“The virtuous circle arises not only from the inherent logic of pluralism and the rule of law, but also because inclusive political institutions tend to support inclusive economic institutions.

This then leads to a more equal distribution of income, empowering a broad segment of society and making the political playing field even more level.

This limits what one can achieve by usurping political power and reduces the incentives to re-create extractive political institutions.

These factors were important in the emergence of truly democratic political institutions in Britain.”

“Meanwhile, the education system, which was previously either primarily for the elite, run by religious denominations, or required poor people to pay fees, was made more accessible to the masses; the Education Act of 1870 committed the government to the systematic provision of universal education for the first time. Education became free of charge in 1891.”

CHAPTER TWELVE: “The Vicious Circle”

“In November 1876, President Barrios wrote to all the governors of Guatemala noting that because the country has extensive areas of land that it needs to exploit by cultivation using the multitude of workers who today remain outside the movement of development of the nation’s productive elements, you are to give all help to export agriculture: From the Indian towns of your jurisdiction provide to the owners of fincas [farms] of workers they need, be it fifty or one hundred.”

“When extractive institutions create huge inequalities in society and great wealth and unchecked power for those in control, there will be many wishing to fight to take control of the state and institutions.

Extractive institutions then not only pave the way for the next regime, which will be even more extractive, but they also engender continuous infighting and civil wars.

These civil wars then cause more human suffering and also destroy even what little state centralization these societies have achieved.”

CHAPTER THIRTEEN: “Why Nations Fail Today”

“The economic and political failure in Zimbabwe is yet another manifestation of the iron law of oligarchy—in this instance, with the extractive and repressive regime of Ian Smith being replaced by the extractive, corrupt, and repressive regime of Robert Mugabe.

Mugabe’s fake lottery win in 2000 was then simply the tip of a very corrupt and historically shaped iceberg.”

CHAPTER FOURTEEN: “Breaking The Mold”

“The most important impetus for change came from the civil rights movement. It was the empowerment of blacks in the South that led the way, as in Montgomery, by challenging extractive institutions around them, by demanding their rights, and by protesting and mobilizing in order to obtain them.”

“At present our objective is to struggle against and crush those persons in authority who are taking the capitalist road, to criticize and repudiate the reactionary bourgeois academic authorities and the ideology of the bourgeoisie and all other exploiting classes and transform education, literature, and art and all other parts of the superstructure that do not correspond to the socialist economic base, so as to facilitate the consolidation and development of the socialist system.”

“China broke the mold, even if it did not transform its political institutions. As in Botswana and the U.S. South, the crucial changes came during a critical juncture—in the case of China, following Mao’s death.”

CHAPTER FIFTEEN: “Understanding Prosperity and Poverty”

“History is key, since it is historical processes that, via institutional drift, create the differences that may become consequential during critical junctures.

Critical junctures themselves are historical turning points. And the vicious and virtuous circles imply that we have to study history to understand the nature of institutional differences that have been historically structured.

Yet our theory does not imply historical determinism—or any other kind of determinism.”

“Small differences and contingency are not just part of our theory; they are part of the shape of history.”

“Even if Chinese economic institutions are incomparably more inclusive today than three decades ago, the Chinese experience is an example of growth under extractive political institutions.

Despite the recent emphasis in China on innovation and technology, Chinese growth is based on the adoption of existing technologies and rapid investment, not creative destruction.”

“One other actor, or set of actors, can play a transformative role in the process of empowerment: the media.

Empowerment of society at large is difficult to coordinate and maintain without widespread information about whether there are economic and political abuses by those in power.”

Book Review (Personal Opinion):

I would consider this more of an encyclopedia than a book. The subject is so broad that it provides a large amount of information and examples.

It is difficult to remember a lot, even after reading it multiple times. However, reading it for the first time gives you a whole new perspective and takes away any rose-colored glasses you may be viewing the world through.

The only reason I didn’t give it a higher rating is that there is a lot of information, which can make it hard to follow the main topic.

Rating: 8/10

This Book Is For:

- Researchers in the political and economic field

- History buffs

- People curious about world development

If You Want To Learn More

TedTalk with the author: Why nations fail | James Robinson | TEDxAcademy

How I’ve Implemented The Ideas From The Book

Since the focus of the book is on the past or the high-level institutions’ work in the present, I am not able to implement any advice directly.

However, what is certain is that my perspective on the world’s monopolies and economy has changed, and I am now much more informed about the situation in the world both in the past and the present.

One Small Actionable Step You Can Do

By reading this book, you can look deeply into the world’s political evolution and take the time to view it from a different perspective. Certainly, if you are doing research, this book can serve as your primary source of information on the subject.